Construction companies often keep two different sets of books—not in the negative sense, but in the sense that one set follows Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and another follows tax rules. Each serves a purpose.

GAAP statements are designed for lenders, bonding companies, and other external stakeholders who need consistent, comparable information. Tax-basis records are designed to calculate income for tax returns. Knowing how they differ helps you decide which you need, when, and why.

For long-term contracts, GAAP typically requires using a form of percentage-of-completion accounting. Revenue and related costs are recognized as work progresses, not just when cash comes in or a project is completed.

In practice, that means:

This approach produces financial statements that better reflect ongoing performance, but it also requires more detailed job costing and regular updates to estimates.

For tax purposes, construction companies may be allowed—or required—to use different methods depending on their size and the nature of their projects. Options can include:

The choice or requirement affects not just timing of tax payments, but also how volatile taxable income appears from year to year.

Construction firms often own significant equipment. GAAP and tax rules treat depreciation differently:

These differences create temporary timing gaps between GAAP income and taxable income. Understanding them matters when explaining results to lenders or planning cash for tax payments.

GAAP requires most longer-term leases to be reflected on the balance sheet as right-of-use assets with corresponding lease liabilities. Rental expense is recognized in a way that spreads cost over the term of the lease.

Tax basis often treats operating leases more simply, with deductions taken as payments are made. The result is that GAAP balance sheets can look heavier—with more assets and liabilities—than tax-basis statements for the same company.

Maintaining GAAP-compliant financial statements requires more effort than simple tax-basis records. It may involve:

Companies often accept that complexity because lenders, bonding companies, or larger customers require GAAP statements. Smaller firms without those demands may choose to operate primarily on a tax basis, at least early on.

For growing construction businesses, there is usually a point where stakeholders begin to ask for more formal reporting. Common triggers include:

At that stage, shifting to GAAP—or enhancing existing GAAP practices—can support those conversations. The move should be deliberate, with clear understanding of what additional information stakeholders expect and how the added clarity can support growth.

Tax-basis records, meanwhile, will remain part of the picture. The question is not which one to use exclusively, but how to manage both in a way that keeps your financial story coherent for each audience that needs to hear it.

A practical comparison of hiring a freelancer vs using a dedicated offshore accounting team, focusing on continuity, quality control, security, and scaling.

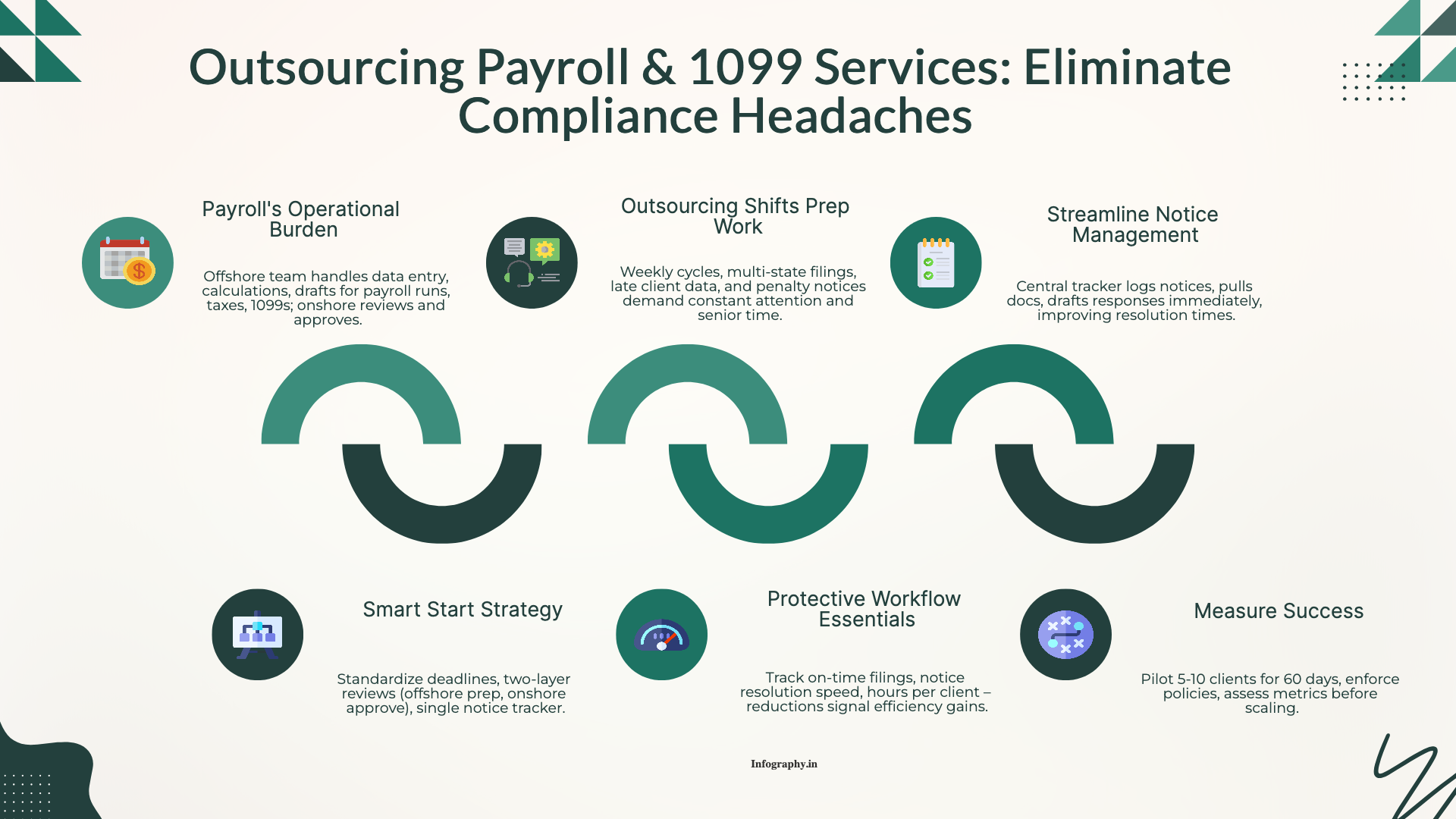

How CPA firms outsource payroll and 1099 work to reduce penalties and admin load, with a clean workflow for approvals, filings, and year-end reporting.

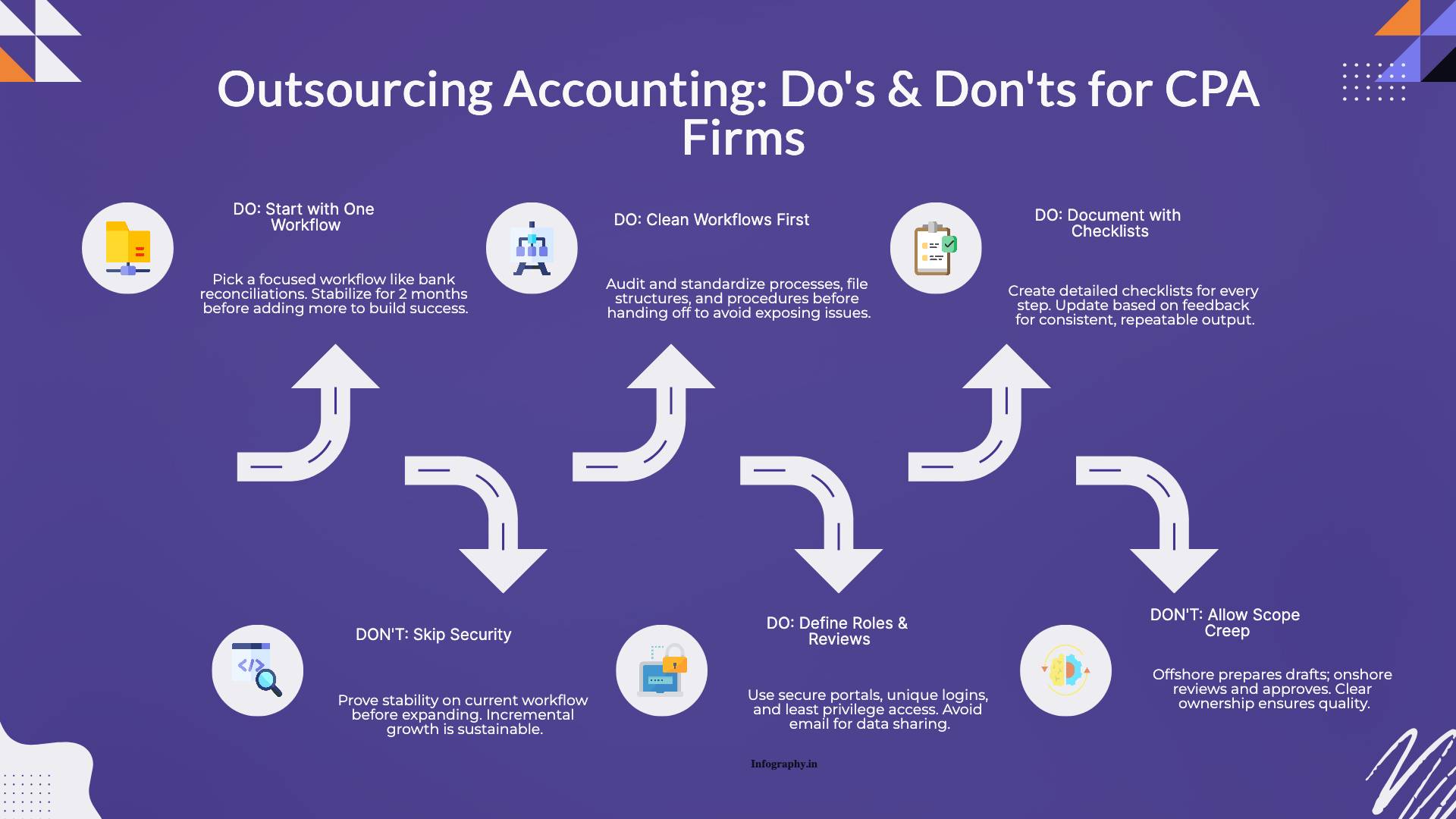

Practical do's and don'ts for CPA firms outsourcing accounting work, based on common failure points and what successful rollouts do differently.