Sending money to another country can feel like navigating a maze of rules and regulations. You might hear terms thrown around that create more confusion than clarity. One such term you may have encountered is the Liberalized Remittance Scheme.

Let’s clear up a common point of confusion right away: The Liberalized Remittance Scheme (LRS) is a set of guidelines from the Reserve Bank of India that allows Indian residents to send up to $250,000 abroad per financial year. It has no direct jurisdiction in the United States.

However, the intent behind searching for this term is universal. You want to know: What are the rules for sending money out of the US? Is there a limit? What do I need to report?

The US system operates very differently from India's LRS. It isn't based on a fixed annual allowance but on principles of transparency and anti-money laundering. This guide will walk you through everything you need to know, dispelling myths and providing a clear path forward for your international transfers. As experts in navigating financial regulations, the team at Madras Accountancy is here to explain the process in simple terms.

Here’s the bottom line: There is no federal limit on the amount of money you can send out of the United States. You can legally send $500,000, $1 million, or more to another country.

The confusion often arises from two sources:

Understanding the difference between a limit and a reporting threshold is the single most important step to confidently sending money abroad.

When you make a transaction involving more than $10,000, it triggers a reporting requirement under the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA). This law is a primary tool for the government to combat financial crimes like money laundering and the financing of terrorism.

If you send or receive more than $10,000 in a single transaction or in a series of related transactions, your financial institution is legally required to file a Currency Transaction Report (CTR) with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), a bureau of the US Treasury.

Here’s what you really need to know about CTRs:

Because the reporting threshold is $10,000, some people think it’s clever to avoid it by sending multiple smaller payments. For example, instead of sending $15,000, they might send two separate transfers of $7,500.

This is called structuring, and it is illegal.

Federal law explicitly prohibits breaking up a large transaction into smaller ones for the purpose of evading reporting requirements. Banks have sophisticated systems designed to detect this activity. Getting caught for structuring can lead to severe penalties, including fines and even jail time. It’s far better to make the single, legal transaction and let the bank file its routine report.

While the bank handles the CTR for the transaction itself, your reporting responsibilities might not end there. These duties are not about the single act of sending money but about the assets you may hold outside the United States as a result.

If your international transfers result in you holding money in foreign accounts, you need to know about the FBAR.

You must file a FinCEN Form 114, Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (FBAR), if you are a "US person" (a citizen, resident, or entity) and the total, aggregate value of all your foreign financial accounts exceeded $10,000 at any point during the calendar year.

Notice the key distinctions:

The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) is another layer of reporting. It requires you to file IRS Form 8938, Statement of Specified Foreign Financial Assets, if you meet certain higher thresholds. These thresholds vary based on your filing status and whether you live in the US or abroad, but they generally start at $50,000.

While there is some overlap with the FBAR, Form 8938 is filed with your IRS tax return and has different requirements. The key takeaway is that significant foreign assets trigger a personal reporting duty to the IRS in addition to the FBAR filing with FinCEN.

Here is a detail that many people miss. If you are sending money to a friend or family member abroad and are not receiving anything in return, that transfer is considered a gift.

The US has a gift tax. For 2024, you can give up to $18,000 to any single individual in a year without any tax implications or reporting requirements. This amount is adjusted periodically for inflation.

What happens if you send more than that annual exclusion amount to one person?

You are required to file Form 709, the United States Gift (and Generation-Skipping Transfer) Tax Return.

Filing this form does not automatically mean you will owe taxes. The US has a very generous lifetime gift and estate tax exemption (over $13 million per individual in 2024). When you file Form 709, you are typically just informing the IRS that you have used up a portion of your lifetime exemption. No tax is due unless you exceed that massive lifetime amount.

Navigating the US system is straightforward when you know the rules. It’s less like India's Liberalized Remittance Scheme and more about simple transparency.

Here is your practical checklist:

The US framework for international remittances is built on trust and transparency. By understanding your role and the bank’s role, you can send funds to loved ones, invest in property, or manage your global finances with complete confidence. For personalized advice on complex international tax and reporting matters, the professionals at Madras Accountancy are always ready to help.

A practical comparison of hiring a freelancer vs using a dedicated offshore accounting team, focusing on continuity, quality control, security, and scaling.

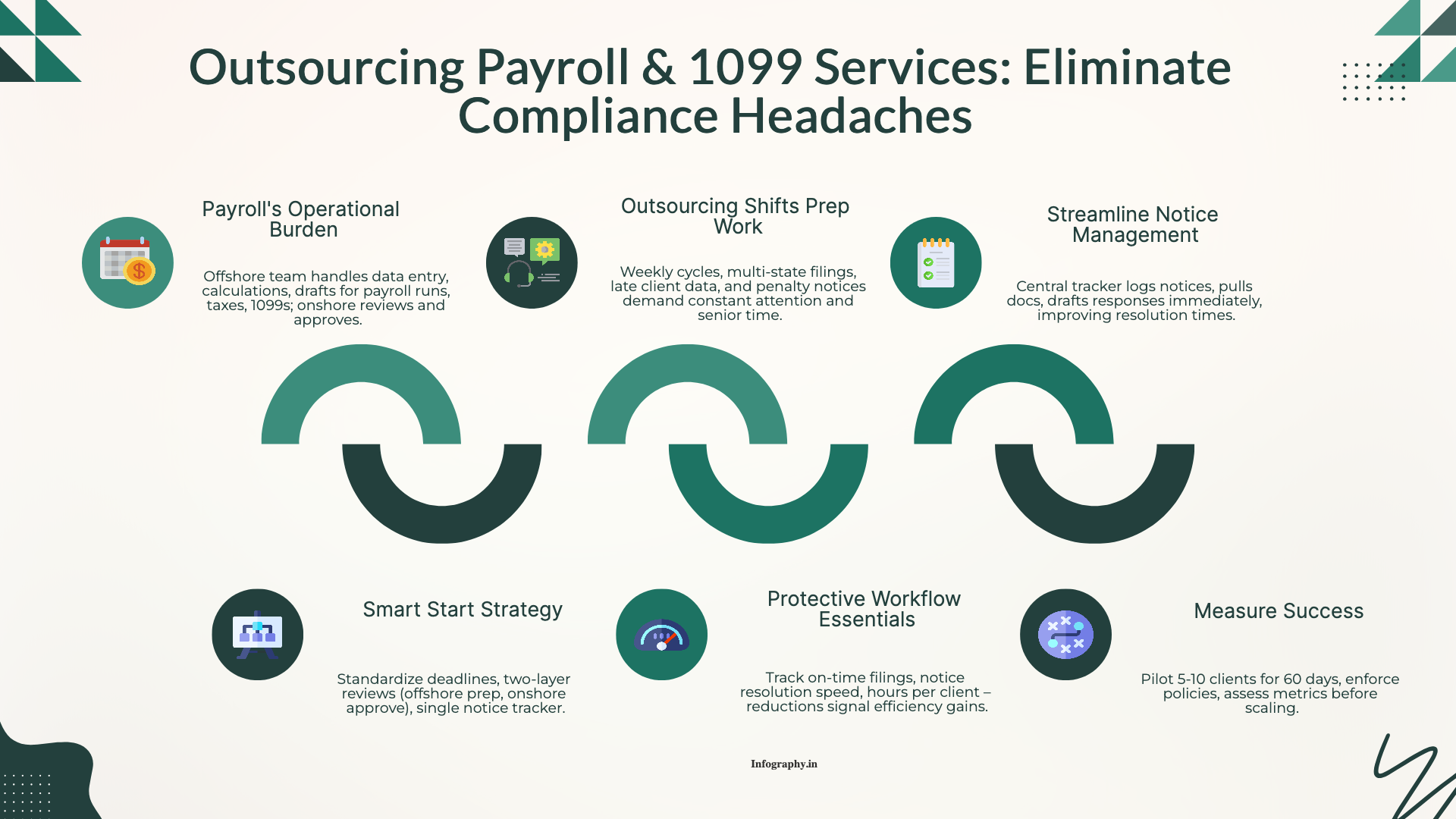

How CPA firms outsource payroll and 1099 work to reduce penalties and admin load, with a clean workflow for approvals, filings, and year-end reporting.

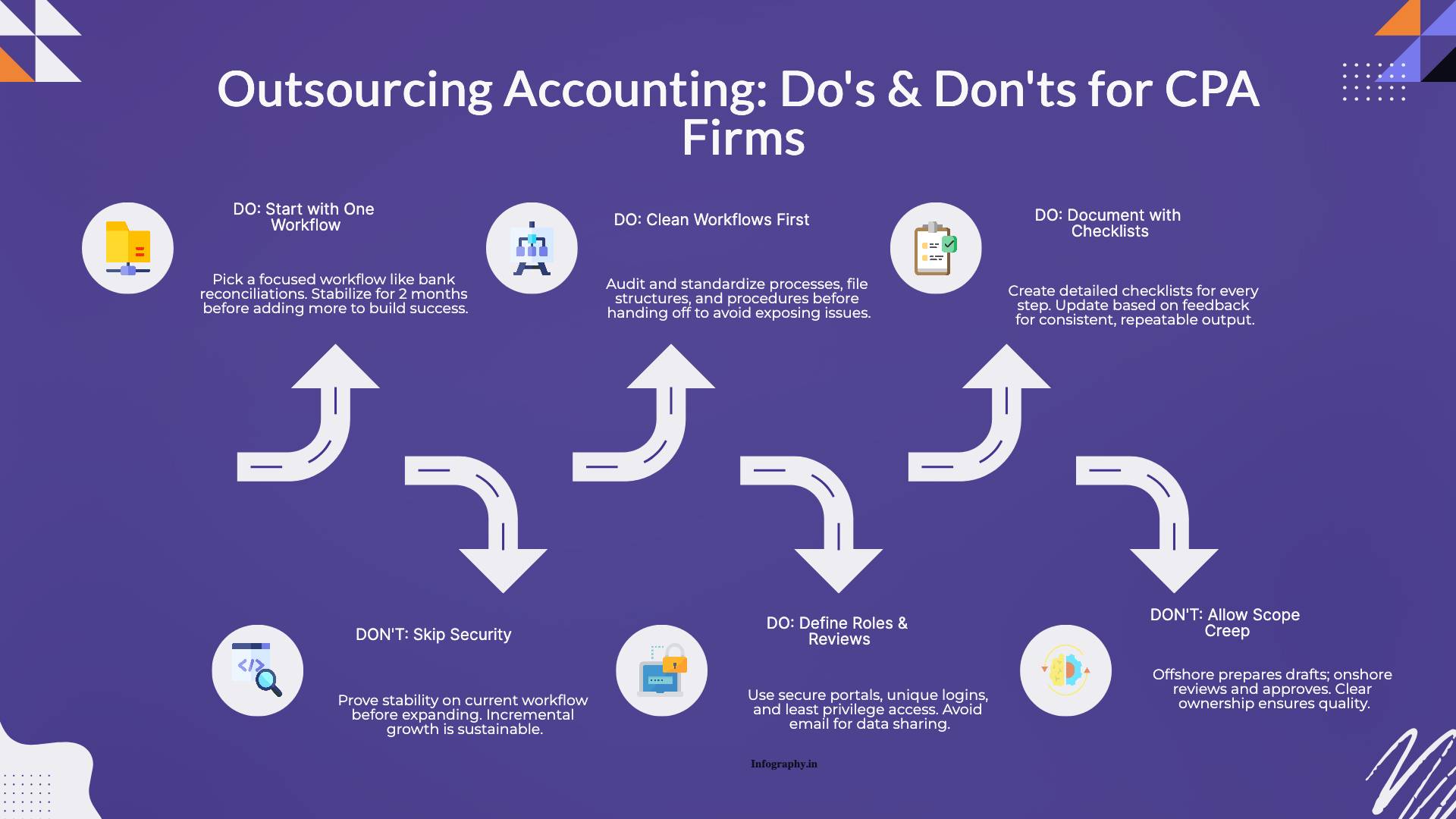

Practical do's and don'ts for CPA firms outsourcing accounting work, based on common failure points and what successful rollouts do differently.