Rental real estate can generate strong cash flow and long-term appreciation, but only if you keep the numbers straight. When records are scattered, categories are inconsistent, or personal and property spending blend together, you pay for it twice—first in stress, then in taxes and missed opportunities.

Clean books do not guarantee good deals, but they give you a clear view of what is working, what is dragging, and where your risk really sits. The most common bookkeeping mistakes in real estate are not complicated. They are habits. Once you recognize them, you can replace them with simple systems that scale as your portfolio grows.

Many investors still rely on a mix of email folders, paper envelopes, and bank statements as their "system." At tax time, they scroll or shuffle through months of transactions, trying to remember which charge was for which property.

That approach might survive one property. It breaks quickly at three or four.

A better pattern is to:

This does not require elaborate tech. It just requires one consistent path for money and documentation instead of many.

Commingling is both an accounting and a legal problem. Paying for a new water heater with your personal card, or using rental income to cover groceries, makes it hard to see what the property truly earns. It also weakens the liability protection you get from an LLC or other structure.

At a minimum, each rental operation should have:

When you accidentally pay a personal expense from the business account, record it promptly as an owner draw. When you cover a property bill from your personal funds, record it as an owner contribution and reimburse yourself. Small corrections made in the same month are far easier than forensic clean-up years later.

Some investors track a single "rental income" line and one big "repairs and maintenance" account for an entire portfolio. That hides which properties are carrying their weight and which are quietly draining time and cash.

Most accounting systems support either separate classes, locations, or tracking categories. Using them, you can:

This structure makes decisions easier. If two properties with similar rents show very different repair histories, you can dig into why. If a new acquisition never reaches expected cash flow, the numbers will show it quickly.

The line between a repair and an improvement matters for tax purposes. Repairs keep a property in its current condition—patching a leak, repainting a room. Improvements extend useful life or increase value—new roofs, additions, major remodels.

Repairs are usually deductible in the year you pay them. Improvements are typically capitalized and depreciated over time. Recording everything as a repair might feel like a short-term win, but it does not match the rules, and it can cause problems in an audit or when the property is sold.

Practical steps:

Purchase and refinance closing statements (HUD-1 or similar) contain line after line of charges—loan fees, prepaid taxes, insurance, recording costs, and more. Many investors simply book the purchase price and move on.

That leaves money on the table. Some of those items are deductible in the year of closing. Others increase your cost basis. Some affect amortization of loan costs.

Instead of treating the statement as a one-time document:

A careful first-year setup makes all future years simpler and more accurate.

Security deposits are not rental income when received. They are liabilities—you owe the money back if the tenant leaves the property in acceptable condition. Treating deposits as income when collected inflates your revenue and creates confusion when tenants move out.

Better practice is to:

This approach aligns with legal requirements in many jurisdictions and keeps your income statement focused on actual earnings.

Depreciation is one of the main tax advantages of owning rental property. It is a non-cash expense that reduces taxable income each year. Skipping or miscalculating it means you pay more tax than necessary, and you still face depreciation recapture rules when you sell.

To handle it well:

Working with a CPA on the initial setup often pays for itself in avoided errors later.

Good real estate bookkeeping is less about having perfect books and more about avoiding predictable, expensive mistakes. Separate business and personal activity, track each property on its own, treat big projects and closing costs with care, and keep depreciation and deposits on a schedule instead of in memory.

When your numbers are organized this way, conversations with lenders, partners, and advisors become much simpler. You spend less time defending rough guesses and more time deciding where to deploy capital next. For more guidance, see our guide on real estate bookkeeping and separating personal and business finances.

A practical comparison of hiring a freelancer vs using a dedicated offshore accounting team, focusing on continuity, quality control, security, and scaling.

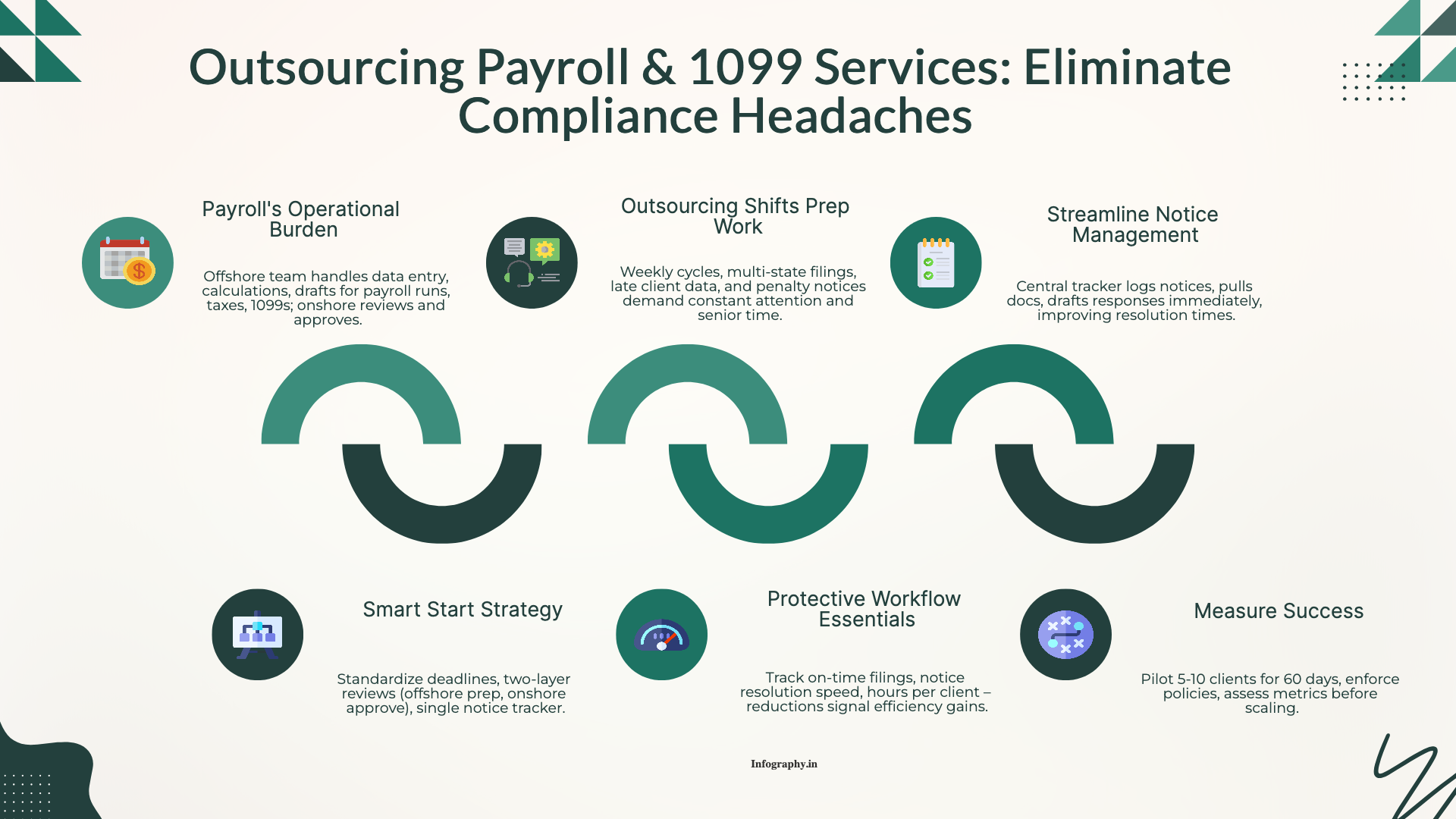

How CPA firms outsource payroll and 1099 work to reduce penalties and admin load, with a clean workflow for approvals, filings, and year-end reporting.

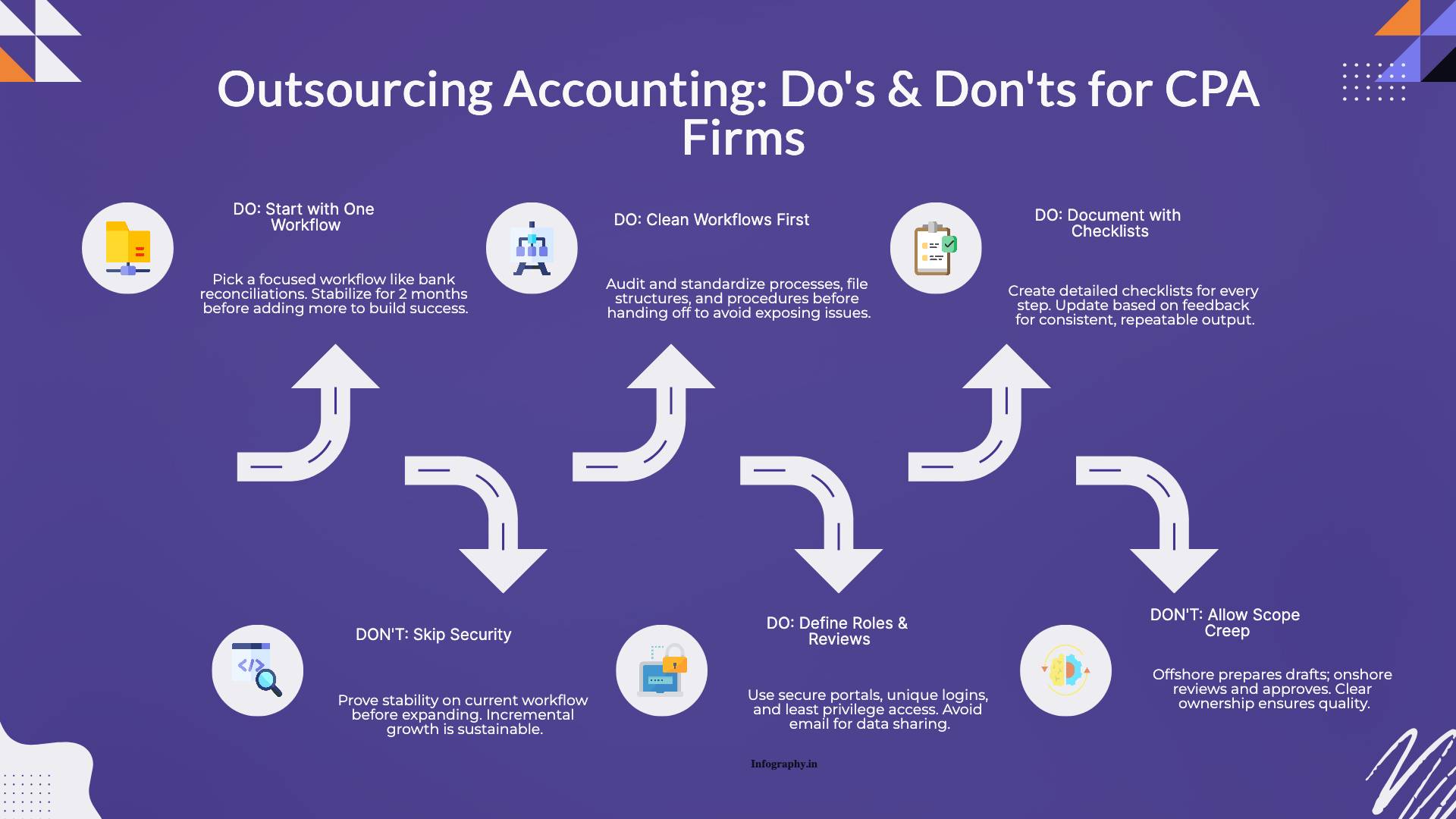

Practical do's and don'ts for CPA firms outsourcing accounting work, based on common failure points and what successful rollouts do differently.