Real estate often starts with a simple act: buying a property in your personal name. That works on paper, but it does not reflect the legal or financial risk involved. The structure you choose—own name, LLC, partnership, or something more complex—shapes how lawsuits reach you, how profits are taxed, and how easy it is to bring in partners later.

You do not have to become a corporate lawyer to choose wisely. You do need a clear sense of what each option actually does and where it tends to fit.

Holding rental property directly, as an individual, is the default. Title lists your personal name, and rental income and expenses flow onto Schedule E of your individual tax return.

On the plus side, this is simple and cheap to set up. There are no separate entity filings or annual fees in most states. For a very small portfolio and modest risk profile, many owners start here.

The trade-off is liability. If something goes wrong at the property—a serious injury or a dispute that escalates—claims can reach beyond the property itself to your personal home, bank accounts, and other assets. Insurance is a first line of defense, but structure adds another layer.

A Limited Liability Company (LLC) is often the first formal step investors take. A single-member LLC with one owner is usually treated as a "disregarded entity" for federal tax purposes. That means you still report income and expenses on Schedule E, but legally, the LLC owns the property.

Advantages include:

The main costs are state filing fees and the discipline to keep finances separate. Casual use of LLC bank accounts for personal spending can weaken the protection you are trying to build.

When more than one person owns a property together, the relationship usually becomes a partnership by default. In practice, most investors formalize that through a multi-member LLC taxed as a partnership.

Key features include:

The additional structure allows for more nuanced arrangements—such as one partner contributing cash and another contributing expertise—but it also brings more paperwork. Tracking capital accounts, documenting contributions and distributions, and maintaining a clear agreement up front reduce confusion later. For more on this, see our guide on joint venture accounting.

S corporations are often discussed in real estate circles because of their potential to reduce self-employment tax on active business income. That can be helpful for activities like flipping, wholesaling, or real estate brokerage, where income is more like business profit than passive rent.

For long-term rental holds, however, S corporations have important downsides:

As a result, many advisors recommend using pass-through entities like LLCs or partnerships for holds, and reserving S corporation structures for active operating income when appropriate.

Most individual investors will not form their own REITs, but it is useful to understand what they are. A REIT is a company that owns or finances income-producing real estate and meets specific regulatory requirements, including distribution of most taxable income as dividends.

For everyday investors, REITs are usually something you buy in a brokerage account to gain exposure to real estate without direct ownership. For sponsors and large portfolios, REIT structures can facilitate raising capital and managing many properties at scale.

What REITs rarely do is serve as the right vehicle for a small number of directly owned rentals. The administrative and regulatory overhead does not match the scale.

As portfolios grow, some investors look beyond single-property LLCs. One common pattern is a holding-company structure in which a parent LLC owns interests in several subsidiary LLCs, each holding one or a group of properties.

This kind of structure can:

The trade-offs are additional filings and more complex accounting. It often makes sense only once your portfolio and risk profile justify the extra layers.

There is no single "right" entity for all real estate investors. Early on, the priority may be to move away from holding properties entirely in your own name. Later, as the number of doors and total equity grow, risk management and partner arrangements start to drive structure choices.

Questions worth asking as you decide include:

Discussing these points with both legal and tax advisors before you form or change entities is almost always cheaper than unwinding a poorly chosen structure later. The goal is not complexity for its own sake. It is a simple, durable framework that protects you and keeps your reporting manageable as you grow. For more on single-member LLC taxation, see our guide.

A practical comparison of hiring a freelancer vs using a dedicated offshore accounting team, focusing on continuity, quality control, security, and scaling.

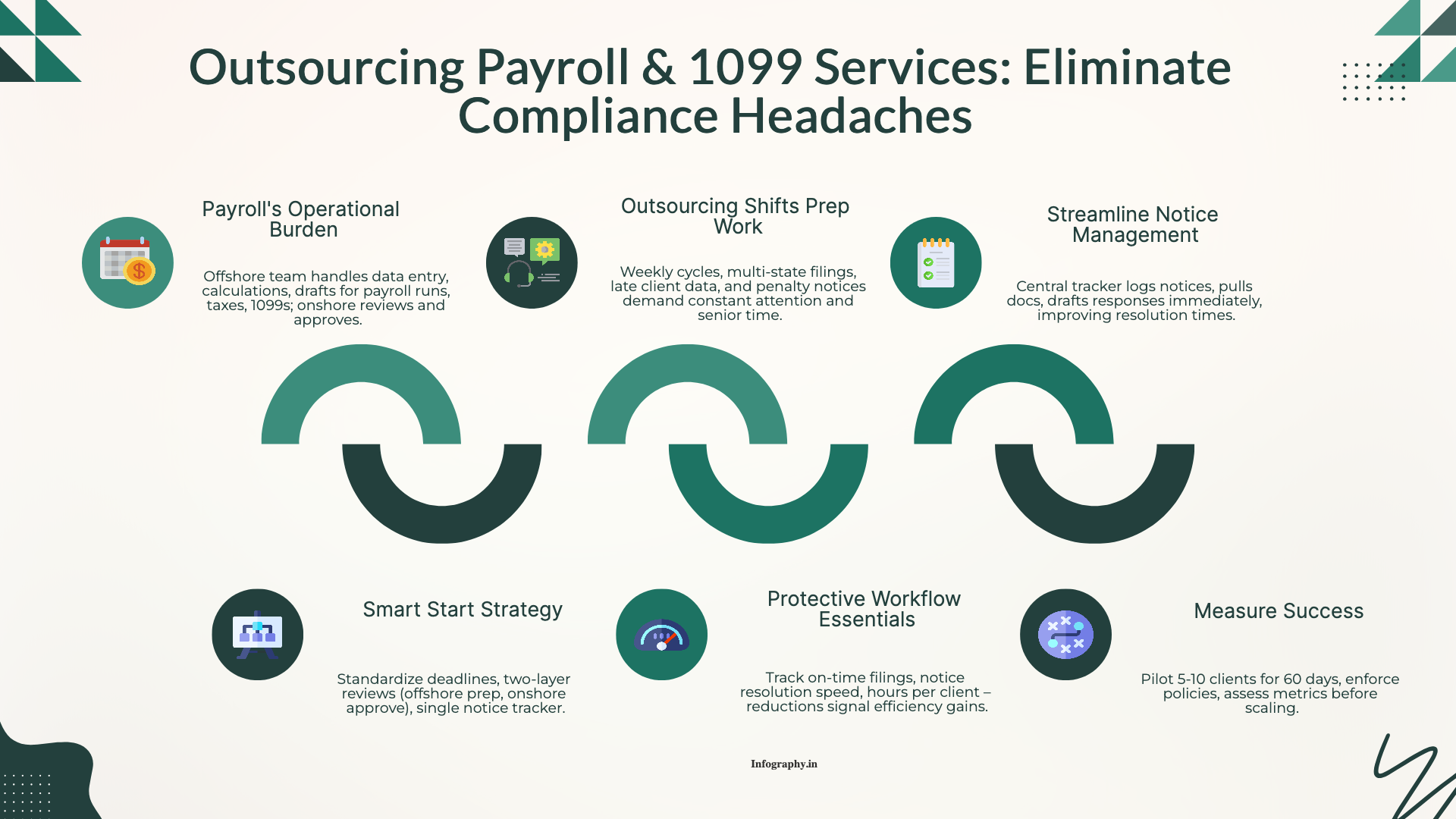

How CPA firms outsource payroll and 1099 work to reduce penalties and admin load, with a clean workflow for approvals, filings, and year-end reporting.

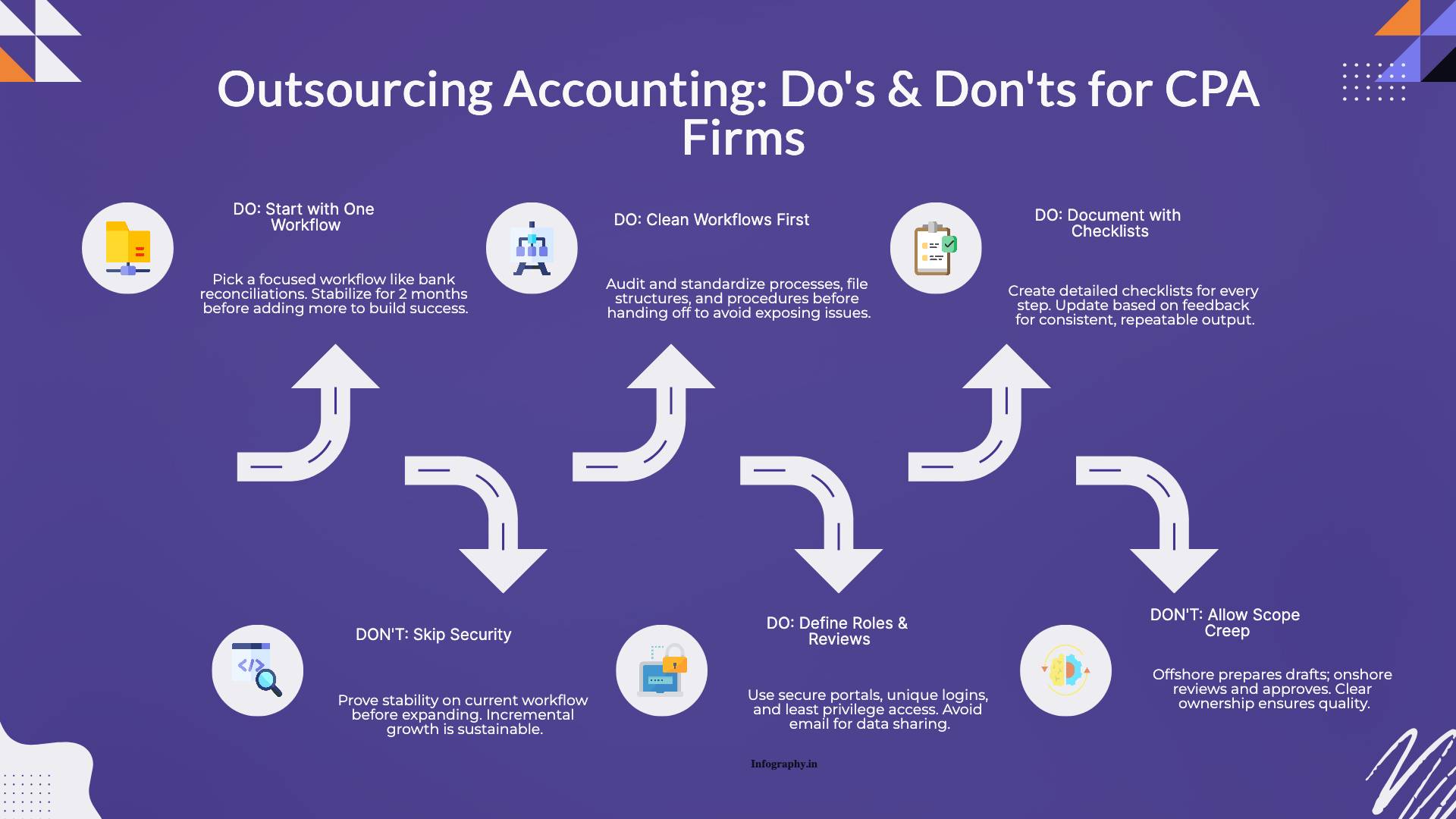

Practical do's and don'ts for CPA firms outsourcing accounting work, based on common failure points and what successful rollouts do differently.