Depreciation is one of the key tax benefits of owning rental real estate. Each year, you deduct a portion of the building's cost, often turning positive cash flow into a paper loss. That feels like free money—until the day you sell and meet depreciation recapture.

Recapture is the mechanism the tax code uses to reclaim some of the benefit you received from prior depreciation deductions. It does not make those past savings disappear, but it does change how part of your gain on sale is taxed. Understanding this before you list a property gives you more room to plan instead of reacting to a surprise bill at closing.

When you buy a rental property, you allocate the purchase price between land (not depreciable) and building (depreciable). Over time, you deduct a portion of the building's cost each year under the applicable recovery period.

Those deductions reduce your tax basis in the property. If you purchased a building for $275,000 (with land valued separately) and claimed $100,000 in depreciation over ten years, your adjusted basis in the building portion drops to $175,000.

When you sell, your total gain is calculated as the difference between the sale price and this adjusted basis, not the original purchase price. The portion of that gain attributable to prior depreciation is subject to special recapture rules.

For residential rental property, the portion of gain equal to the depreciation you claimed (or could have claimed) is generally taxed at a rate of up to 25%. The rest of the gain—above and beyond prior depreciation—is typically taxed at long-term capital gains rates if you held the property for more than one year.

In a simple example:

Total gain is $225,000. Of that, $100,000 is subject to the recapture rules (up to 25%), and $125,000 is taxed at the applicable capital gains rate. The exact blend depends on your overall income and other factors, but the key takeaway is that not all of the gain enjoys the lower capital gains rate.

Some owners think they can avoid recapture by not claiming depreciation. The tax code does not support that idea. Depreciation is treated as "allowed or allowable," which means that even if you fail to claim deductions you were entitled to, your basis is still reduced as if you had.

In practice, that leads to the worst of both worlds: you miss out on valuable deductions during ownership and still face recapture at sale. If you discover that you have not been taking depreciation, it is usually worth talking with a tax professional about corrective steps rather than ignoring the issue.

You cannot make recapture disappear with a simple election, but you can use planning tools to manage its impact as part of an overall exit strategy.

A properly structured like-kind exchange under Section 1031 allows you to defer both capital gains and depreciation recapture by rolling your equity into a new qualifying property. The tax basis and accumulated depreciation effectively carry over to the replacement property.

Key considerations include strict timelines for identifying and closing on replacement properties, using a qualified intermediary to hold proceeds, and ensuring that the value and debt of the new property are sufficient to avoid "boot" that might trigger partial gain recognition.

If you hold other investments with unrealized losses, such as securities or underperforming assets, you might consider realizing some of those losses in the same year as your property sale. While capital losses do not offset depreciation recapture directly at a different rate, they can still reduce your overall taxable income from gains, softening the combined impact.

Installment sales, where you receive payments over time, spread capital gains recognition across multiple years. However, depreciation recapture is generally recognized in the year of sale, even if much of the cash arrives later.

That means you need enough cash up front from the buyer's down payment to cover the recapture tax, or access to other funds. An installment sale that ignores this can create a mismatch between tax obligations and liquidity.

Depreciation recapture is a built-in feature of rental property taxation. Viewed in isolation, it can feel like a penalty. Viewed over the full life of the investment, it represents in part the trade-off for years of reduced taxable income.

The most practical approach is straightforward: project your likely gain and recapture before listing a property, explore whether an exchange or coordinated planning with other assets makes sense, and align your sale timing with your broader financial picture. With that preparation, the "hidden" tax becomes simply one more variable you have already accounted for, rather than an unwelcome surprise when you are already committed to selling. For more on exit strategies, see our guide on 1031 exchanges and exit strategy modeling.

A practical comparison of hiring a freelancer vs using a dedicated offshore accounting team, focusing on continuity, quality control, security, and scaling.

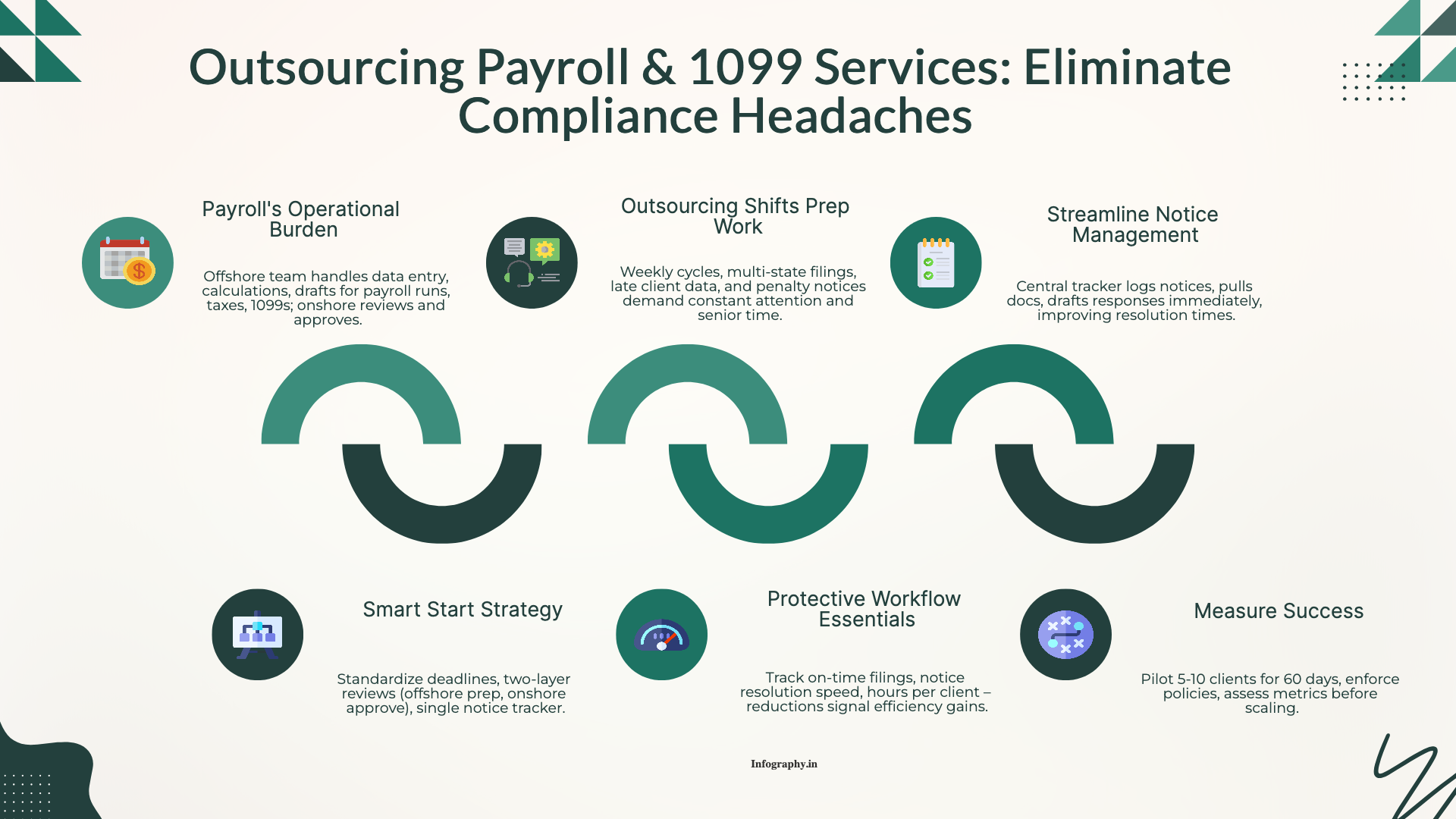

How CPA firms outsource payroll and 1099 work to reduce penalties and admin load, with a clean workflow for approvals, filings, and year-end reporting.

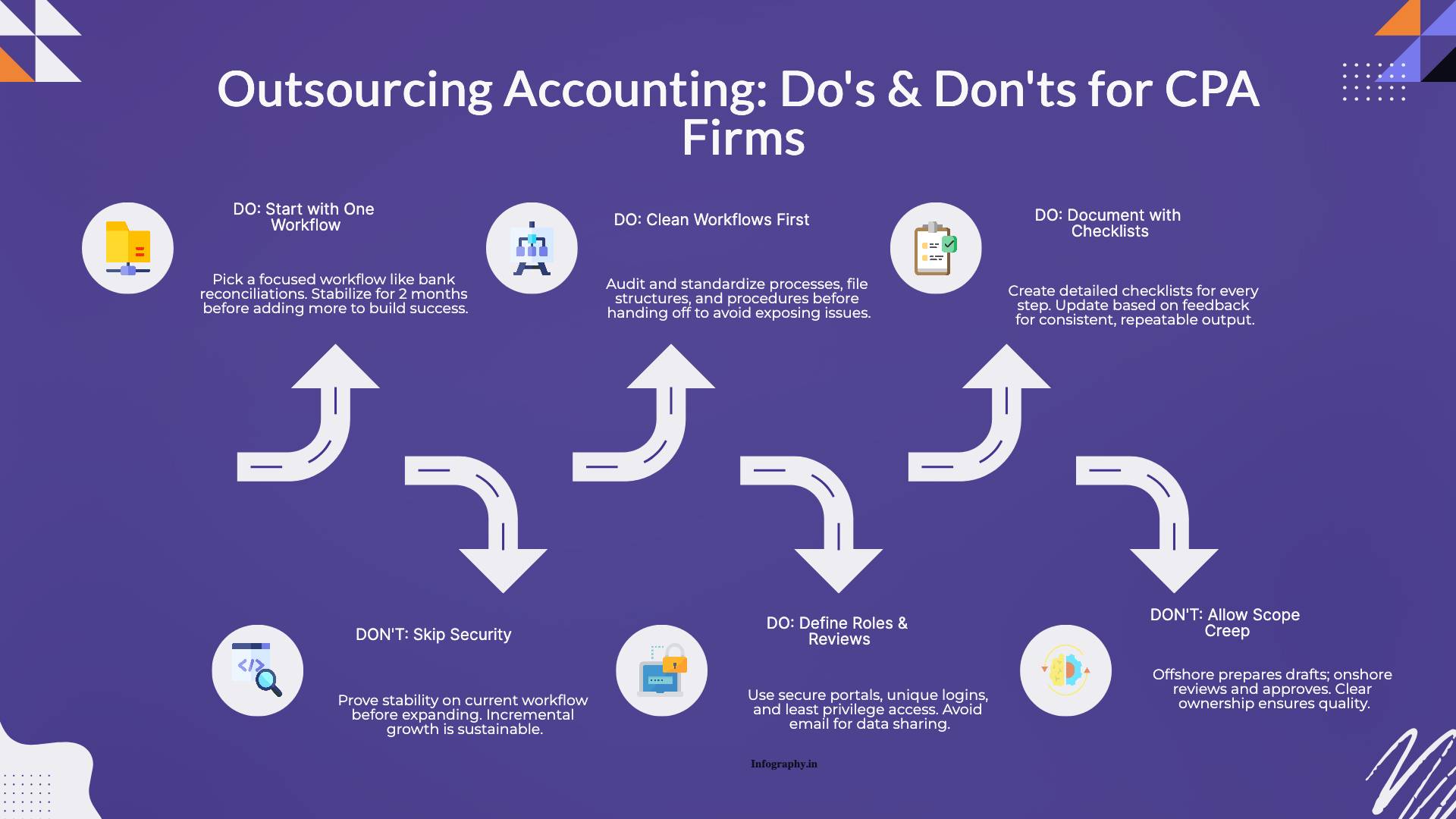

Practical do's and don'ts for CPA firms outsourcing accounting work, based on common failure points and what successful rollouts do differently.