The first time a lender or investor says, "We need audited financial statements," many owners picture someone in a dark suit hunting for problems. The word "audit" carries a certain weight, thanks in part to tax authorities.

A financial statement audit from a CPA firm is different. The goal is to provide an independent opinion on whether your financial statements are fairly stated. That still means work on your side, but it does not have to be a crisis. With some planning, the process can feel structured instead of chaotic.

First, be clear about the scope. An external financial audit is not a forensic investigation, and it is not designed primarily to detect fraud. It is also not a full consulting project that will redesign your systems for you.

The auditor's job is to gather enough evidence to say whether the statements, as a whole, are reasonable. They focus on material items, meaning numbers big enough to matter to a reader. Small errors may be noted but not always adjusted if they do not change the overall picture.

Shortly after you engage an audit firm, they will send a list of items they need you to provide. This is often called the PBC list, short for "prepared by client." It usually includes trial balances, bank statements, loan agreements, major contracts, and support for key accounts like receivables and inventory.

Do not wait until the week before fieldwork to open that list. Instead, sit down with your internal team and assign responsibilities. Who will pull bank confirmations? Who will reconcile inventory counts? Treat the list as a project plan rather than a last minute to do stack.

Auditors work best when they are testing a stable set of numbers. If your accounting records for the year are still changing while they are onsite or logged in, everyone gets frustrated.

Aim to have the year closed and reviewed internally before the auditors begin detailed work. That means all routine entries are posted, reconciliations are done, and obvious questions have been cleared up. You do not need perfection, but you should not be making large basic corrections during the audit window if you can avoid it.

One practical way to stay sane is to set up digital folders that mirror your trial balance. For example, have separate folders for cash, receivables, inventory, fixed assets, payables, debt, and equity. Store bank statements, aging reports, contracts, and other support in those folders.

When auditors ask, "Can we see support for this balance?" you will know exactly where to look. This also helps your own team understand how each balance is built up, which is valuable even outside of audit season.

If you know there are problem areas, such as messy inventory records or a new revenue recognition pattern you are not entirely sure about, tell the auditors early. Surprises discovered on the last day of fieldwork are the ones that delay reports.

Most audit teams would rather hear, "We are not fully confident in this area, can you walk us through how you will test it?" than pretend everything is perfect. Honest discussion helps everyone plan the work more realistically.

Finally, treat the first audit as a learning opportunity. Ask questions about what the auditors are testing and why. When they recommend control improvements or process tweaks, take those seriously. Many of the best accounting systems in mature companies were shaped over time by audit feedback.

By the second or third year, the audit will feel far less mysterious. The first one is about getting over the hump, building your documentation muscles, and proving to outside parties that your numbers can hold up to a professional look. For more insights, see our guide on internal vs external audits and common audit issues small businesses face.

A practical comparison of hiring a freelancer vs using a dedicated offshore accounting team, focusing on continuity, quality control, security, and scaling.

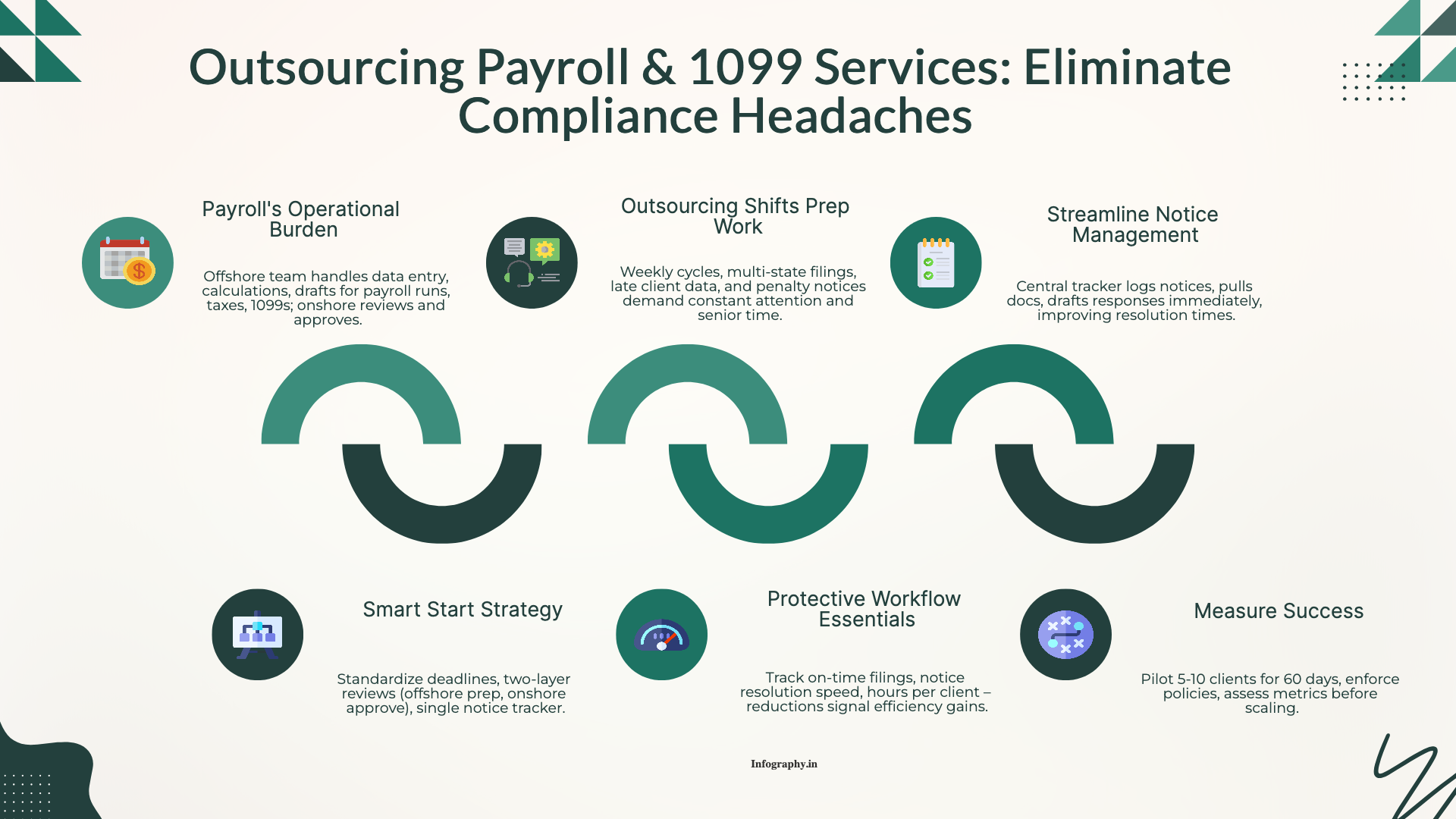

How CPA firms outsource payroll and 1099 work to reduce penalties and admin load, with a clean workflow for approvals, filings, and year-end reporting.

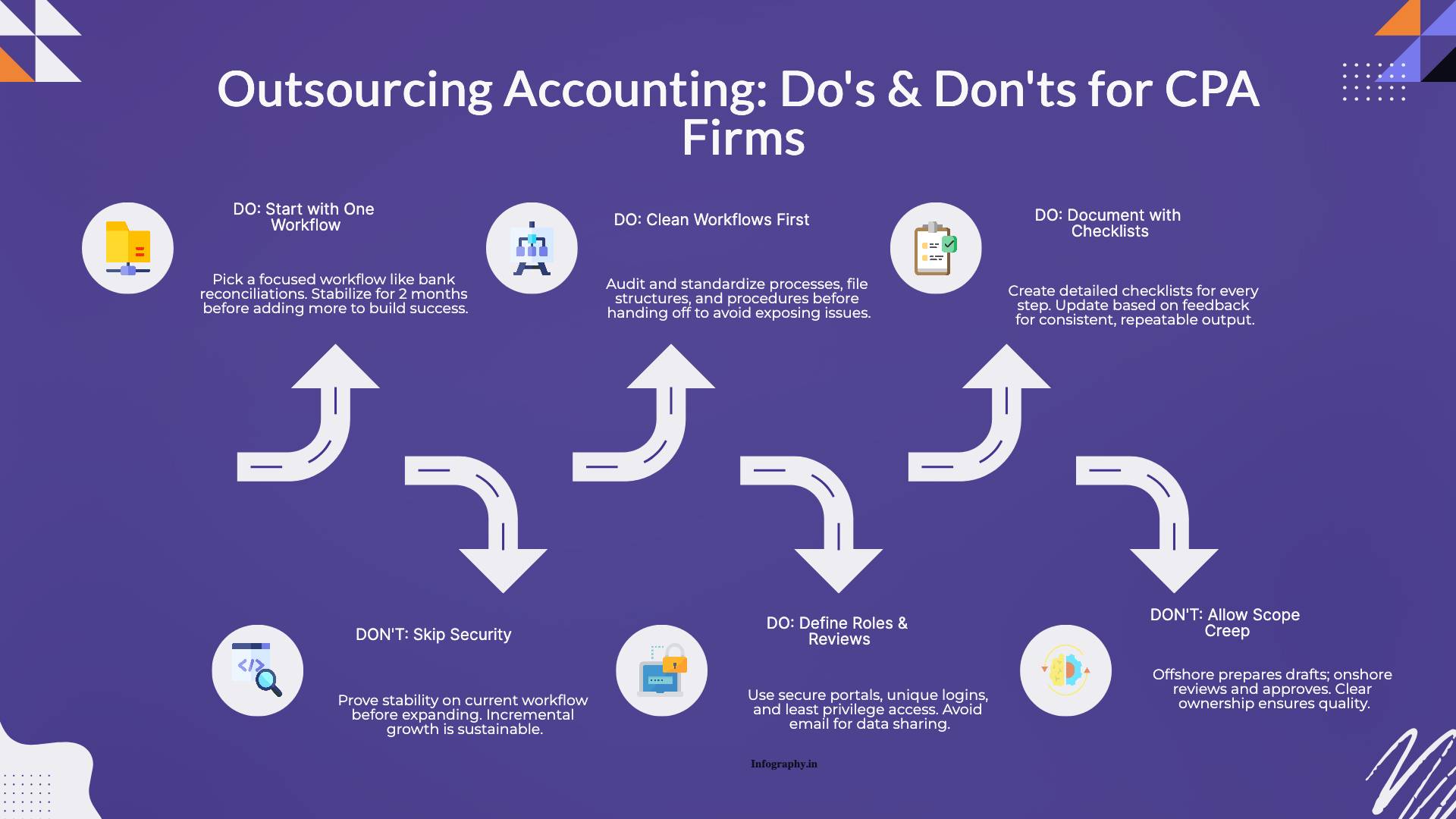

Practical do's and don'ts for CPA firms outsourcing accounting work, based on common failure points and what successful rollouts do differently.