Cost cutting stories often exaggerate results or cherry-pick favorable comparisons. This is not one of those stories. This is a composite based on patterns observed across small and mid-sized CPA firms that implemented outsourcing thoughtfully, measured results honestly, and achieved substantial cost reductions while maintaining or improving quality. The numbers are worked examples with stated assumptions, not guarantees, but they reflect realistic outcomes when outsourcing is executed well.

The fifty percent cost reduction referenced in the title is not a reduction in total payroll. It is a reduction in cost per unit of output, which is a more meaningful measure of efficiency. When a firm can handle more clients or more returns with the same or lower production costs, the unit economics improve dramatically even if absolute costs decline more modestly.

The firm employed ten people total, including partners, managers, and staff. The client base was strong and loyal. The problem was capacity. The firm was turning away prospective clients because they lacked the staff to serve them without compromising service quality for existing clients. Payroll was consuming margin because the firm was paying market rates for talent in a competitive hiring environment.

Bookkeeping work was expanding faster than the firm could hire. Clients were growing their businesses, adding complexity, and generating more transactions. Each client required more hours than in prior years, but fee increases were not keeping pace with the time investment. The firm needed more capacity but could not afford to keep adding full-time staff at current market rates.

Tax season required significant overtime and temporary help. Seasonal workers needed supervision, which pulled managers away from review and client work. The temps were expensive, inconsistent in quality, and required retraining every year because turnover was complete. This model was not sustainable.

The firm employed two in-house accounting staff focused primarily on bookkeeping and tax preparation support. These were not entry-level roles. They required three to five years of experience, knowledge of accounting software, and the ability to work independently on routine tasks. In the firm's market, base salary for these roles was eighty thousand dollars annually.

Benefits and payroll burden added approximately twenty-five percent to the base salary. This included health insurance, retirement contributions, payroll taxes, and paid time off. The fully loaded cost per role was one hundred thousand dollars. For two roles, the total annual cost was two hundred thousand dollars.

This baseline does not include the cost of recruiting, which took months and often required working with recruiters who charged substantial fees. It does not include turnover risk, which was real because staff accountants in this market were in high demand and frequently received competing offers. It does not include the manager time spent fixing errors, answering questions, and cleaning up work that junior staff struggled to complete under time pressure.

The firm replaced one full-time role with an offshore team member and shifted the remaining in-house staff member from pure production work to review and client-facing responsibilities. This was not a simple substitution. It required restructuring workflows, documenting processes, and training both the offshore team and the onshore staff on their new responsibilities.

The offshore team member cost forty-two thousand dollars annually, inclusive of all fees charged by the outsourcing provider. This rate reflected a mid-tier provider with quality controls, training programs, and account management support. Cheaper providers exist, but the firm prioritized quality over rock-bottom pricing.

The direct cost change was straightforward. Before outsourcing, the firm spent two hundred thousand dollars annually on these two roles. After outsourcing, the firm spent one hundred thousand dollars for one in-house role plus forty-two thousand dollars for the offshore role, totaling one hundred forty-two thousand dollars. The estimated savings were fifty-eight thousand dollars, or twenty-nine percent of the baseline cost.

This twenty-nine percent savings is significant, but it is not the fifty percent referenced in the title. That larger figure comes from looking at cost per unit of output rather than absolute costs.

The firm used outsourcing not just to reduce costs, but to increase output capacity with the same onshore team size. This is where the economics become compelling. Before the change, the firm handled thirty-five monthly bookkeeping clients and prepared six hundred fifty tax returns annually. These volumes reflected the capacity limits of the two in-house staff members, who were working at full capacity during peak periods and moderately busy during slower periods.

After workflow stabilization, which took approximately four months, the firm handled fifty-five monthly bookkeeping clients and prepared eight hundred tax returns annually. The increase in capacity came from several sources. The offshore team handled more hours because they were dedicated full-time to production work without the distractions of internal meetings, training sessions, or administrative tasks that consume time in a small firm.

The in-house staff member who shifted to review was able to review work faster than they could produce it from scratch, creating a leverage effect. One person reviewing could support the output of two or three people drafting, which meant the firm could add more offshore capacity without needing to add onshore reviewers proportionally.

The workflow became more efficient because processes were documented, standardized, and followed consistently. The offshore team used checklists, templates, and structured workflows that reduced errors and made review faster. This process improvement was a byproduct of outsourcing because the firm was forced to document what had previously existed only in the heads of experienced staff.

When you calculate cost per bookkeeping client supported, the improvement is dramatic. Before outsourcing, the cost was two hundred thousand dollars divided by thirty-five clients, or approximately five thousand seven hundred fourteen dollars per client annually in production costs. After outsourcing, the cost was one hundred forty-two thousand dollars divided by fifty-five clients, or approximately two thousand five hundred eighty-two dollars per client annually. This represents a fifty-five percent reduction in cost per client.

For tax returns, the math is similar. Before outsourcing, the cost per return was two hundred thousand dollars divided by six hundred fifty returns, or approximately three hundred eight dollars per return. After outsourcing, the cost per return was one hundred forty-two thousand dollars divided by eight hundred returns, or approximately one hundred seventy-eight dollars per return, a forty-two percent reduction.

The cost reduction was significant, but it was not the only benefit. The firm eliminated overtime costs because the offshore team absorbed surge capacity during tax season. Previously, the in-house staff worked extensive overtime at time-and-a-half rates, and the firm hired temporary workers who required supervision. With the offshore team handling peak volume, overtime dropped dramatically and temp costs were eliminated entirely.

Turnover risk decreased because the firm no longer relied on two critical in-house roles where departure would create immediate crisis. The offshore provider managed staffing, backup, and continuity. If one offshore team member was unavailable, another stepped in. The firm's operational risk was distributed rather than concentrated in one or two people.

Manager time was freed for higher-value work. Before outsourcing, managers spent significant time fixing errors, answering basic questions, and redoing work that junior staff struggled to complete correctly. After outsourcing, the offshore team produced cleaner, more consistent work because they followed documented processes and received regular training from the provider. Manager review time decreased, and the freed capacity went toward client advisory work and business development.

The cost savings were not automatic. They resulted from deliberate decisions and disciplined execution. The firm standardized processes before outsourcing began, creating checklists, templates, and documentation that made training efficient and quality consistent. They chose a provider based on quality and track record rather than lowest price, recognizing that poor quality would erase cost savings through rework.

They measured results honestly, tracking cost per client, cost per return, rework rates, and client satisfaction. When issues emerged, they addressed them quickly rather than letting problems compound. They protected the time that outsourcing freed up, directing it toward revenue-generating activities rather than allowing it to fill with low-value busywork.

The fifty percent cost reduction was real, but it was measured correctly as cost per unit of output, not as a simple headcount substitution. That distinction matters because it reflects the true economic value of outsourcing: the ability to handle more work with lower per-unit costs while maintaining quality and reducing operational risk.

A practical comparison of hiring a freelancer vs using a dedicated offshore accounting team, focusing on continuity, quality control, security, and scaling.

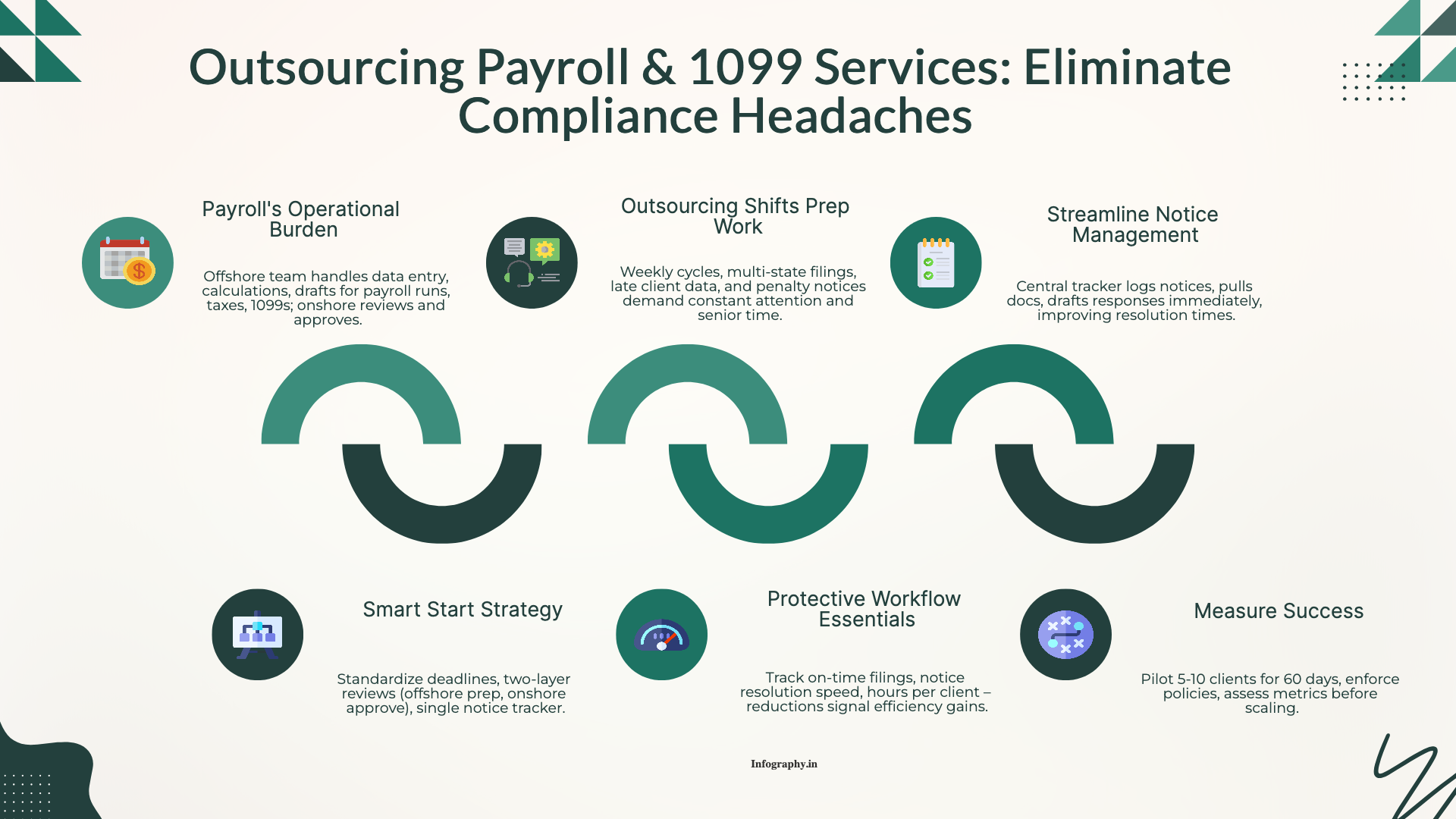

How CPA firms outsource payroll and 1099 work to reduce penalties and admin load, with a clean workflow for approvals, filings, and year-end reporting.

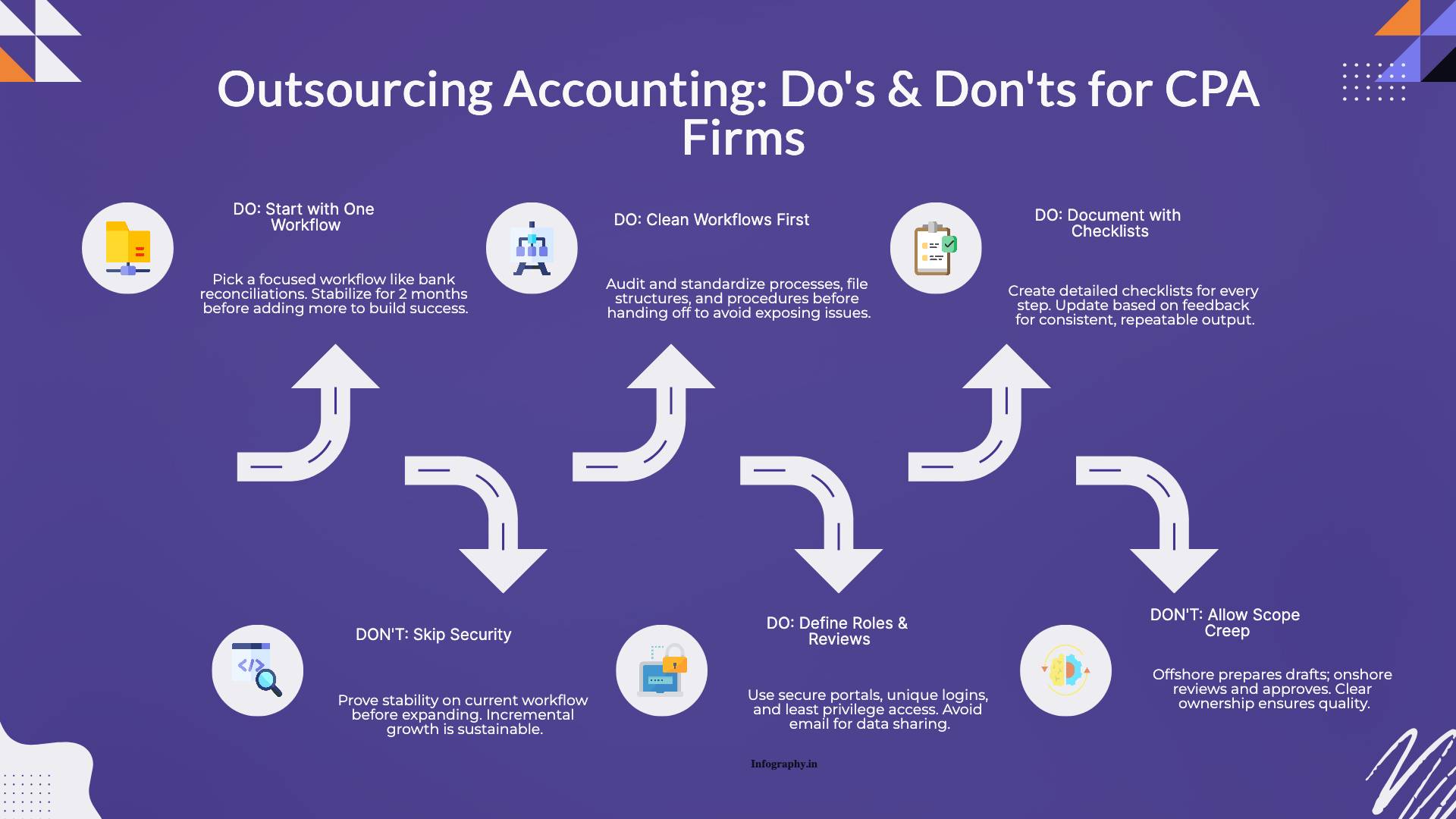

Practical do's and don'ts for CPA firms outsourcing accounting work, based on common failure points and what successful rollouts do differently.