Capacity constraints are rarely a single dramatic bottleneck. They manifest as a chain of small delays that accumulate until the firm declares they are at capacity and cannot take on new clients. A few days slip on month-end close deadlines. Managers spend more time cleaning up mistakes than reviewing work. Client service quality declines because no one has time to return calls promptly. Eventually, the firm stops marketing because they know they cannot serve additional clients without sacrificing quality for existing ones.

Scaling capacity is not about working faster or hiring faster. It is about reorganizing workflows so the existing team can handle higher volume without proportional increases in effort. Outsourcing is one of the tools that makes this reorganization possible, but only if implemented thoughtfully with clear processes and quality controls. This is not a case study of a specific firm, but a composite story based on patterns observed across firms that successfully doubled their client capacity through outsourcing.

The firm supported approximately one hundred recurring clients with a stable core team of partners, managers, and senior accountants. Client retention was strong, and the quality of work was solid. The problem was not performance. The problem was growth, or rather the lack of it. The firm had strong demand from prospective clients, but onboarding new clients created immediate operational stress.

Bookkeeping and close work expanded faster than the firm could hire. Each new client added hours of transaction coding, reconciliation, and financial statement preparation to the workload. The firm hired when they could find qualified candidates, but recruiting took months, and training new staff took even longer. By the time a new hire was productive, the backlog had grown again.

Managers spent too much time cleaning up work instead of reviewing it. Junior staff were overwhelmed and making errors. Managers ended up redoing reconciliations, correcting journal entries, and fixing categorization mistakes rather than focusing on review, coaching, and client advisory work. This misallocation of senior talent created a double problem: junior staff were not improving because they lacked proper training, and managers were too busy fixing problems to do strategic work.

The firm added an offshore team to handle the preparation layer of work, specifically the tasks that consumed the most time but required the least judgment. The offshore team was not a replacement for the onshore staff. It was an extension of capacity that allowed the onshore team to shift their focus from production to review and client service.

The offshore team handled transaction coding and cleanup, taking raw bank feeds and receipts and coding them to the correct accounts according to the firm's chart of accounts standards. They handled reconciliations and balance sheet support, preparing bank reconciliations, credit card reconciliations, and account analysis schedules. They prepared first draft financial statements based on the reconciled data, generating balance sheets, income statements, and cash flow statements in the firm's standard format.

The onshore staff retained responsibility for everything that required judgment, client interaction, or regulatory accountability. They handled all client communication, including monthly calls, questions about transactions, and strategic discussions. They reviewed the work prepared by the offshore team, investigating exceptions, addressing discrepancies, and ensuring accuracy before anything was finalized or sent to clients. They maintained final delivery responsibility and sign-off authority.

Before outsourcing, the firm spent approximately twelve hours per month per client on bookkeeping and close support. For one hundred clients, that totaled twelve hundred hours per month of onshore staff time. This time included transaction coding, reconciliations, financial statement preparation, review, and client communication.

After implementing outsourcing, the firm moved roughly 55 percent of the production work to the offshore team. This included the initial transaction coding, reconciliation preparation, and draft financial statement generation. The onshore team still needed to handle review, exceptions, and client communication, which represented about 35 percent of the original time investment. Some efficienc ies were gained in review because the offshore team's work was more consistent and better documented than the rushed work of overwhelmed junior staff.

The estimated onshore hours after the shift were approximately four hundred twenty hours per month, calculated as twelve hundred hours multiplied by 35 percent. This is a worked example with clear assumptions, not a guarantee. The actual time savings depend on client mix, workflow complexity, and how well the processes are documented. The core principle is that onshore hours shift from production to review, and the per-client time requirement decreases substantially.

The firm used the freed capacity to onboard more clients rather than reduce staff or hours. They did not change their pricing. They changed their throughput. With the onshore team spending less time on production and more time on review and advisory, they could handle a higher volume of clients without compromising quality.

Over time, the client count increased from one hundred to two hundred without doubling onshore headcount. The offshore capacity scaled with volume because the provider could add team members as needed. The onshore team grew modestly, adding a few senior accountants and one manager, but the growth in staff was far less than the growth in clients. The economics of the business improved because revenue grew faster than costs.

Scaling capacity through outsourcing is not automatic. It requires operational discipline and process standardization that many firms lack initially. The firms that successfully scale build systems that make higher volume manageable.

Standard intake packets for new clients were essential. Every new client received the same onboarding checklist, the same request for documentation, and the same explanation of the workflow. This consistency allowed the offshore team to onboard new clients quickly because they knew exactly what to expect and what questions to ask. It also set clear expectations with clients about what information they needed to provide and when.

One workflow tracker for all tasks created visibility and accountability. The tracker showed which clients were in progress, which were waiting for information, and which were complete. Both the onshore and offshore teams updated the tracker in real time, so everyone knew the status of every client without needing constant status meetings. This transparency reduced communication overhead and prevented work from getting lost.

Fixed review windows each day created predictability. Instead of reviewing work whenever it arrived, the onshore team set specific times each day for review. The offshore team knew that work submitted by a certain time would be reviewed that day, and feedback would be provided by the next morning. This rhythm allowed the offshore team to plan their work and learn from feedback quickly.

Templates for recurring workpapers standardized output and reduced the cognitive load on both teams. Every bank reconciliation followed the same format. Every financial statement package included the same schedules in the same order. Templates made training faster, review easier, and quality more consistent because deviations from the standard format were immediately obvious.

Scaling can fail if quality declines as volume increases. The firms that avoid this trap maintain rigorous review standards and tighten processes as they grow. The firm in this example kept quality stable by ensuring that review and sign-off remained entirely in-house, performed by experienced staff who understood the firm's standards and the clients' businesses.

As client volume grew, the firm refined its checklists to address recurring errors and edge cases. When the same review note appeared multiple times, the checklist was updated to prevent that error from recurring. This continuous improvement approach meant that quality standards actually strengthened as the firm scaled, rather than weakening as would happen if growth outpaced process development.

Measure current hours per client for one service line to establish a baseline. Track how much time is spent on production versus review. This measurement reveals where the bottlenecks are and where outsourcing can have the most impact.

Outsource drafting work for a pilot group of clients, starting with five to ten clients who have similar complexity and workflows. Do not try to scale the entire book at once. Prove the model works at small scale before expanding.

Track rework rates and cycle time for at least four weeks. Rework rates show whether the offshore team is producing quality work. Cycle time shows whether the workflow is actually faster or just redistributed. If both metrics improve, expand the scope gradually. If they do not, diagnose the problem before scaling further.

Doubling capacity is possible, but it is not automatic. It is the result of deliberate workflow design, process standardization, and disciplined execution. Firms that treat outsourcing as a strategic operating model rather than a staffing band-aid are the ones that successfully scale.

A practical comparison of hiring a freelancer vs using a dedicated offshore accounting team, focusing on continuity, quality control, security, and scaling.

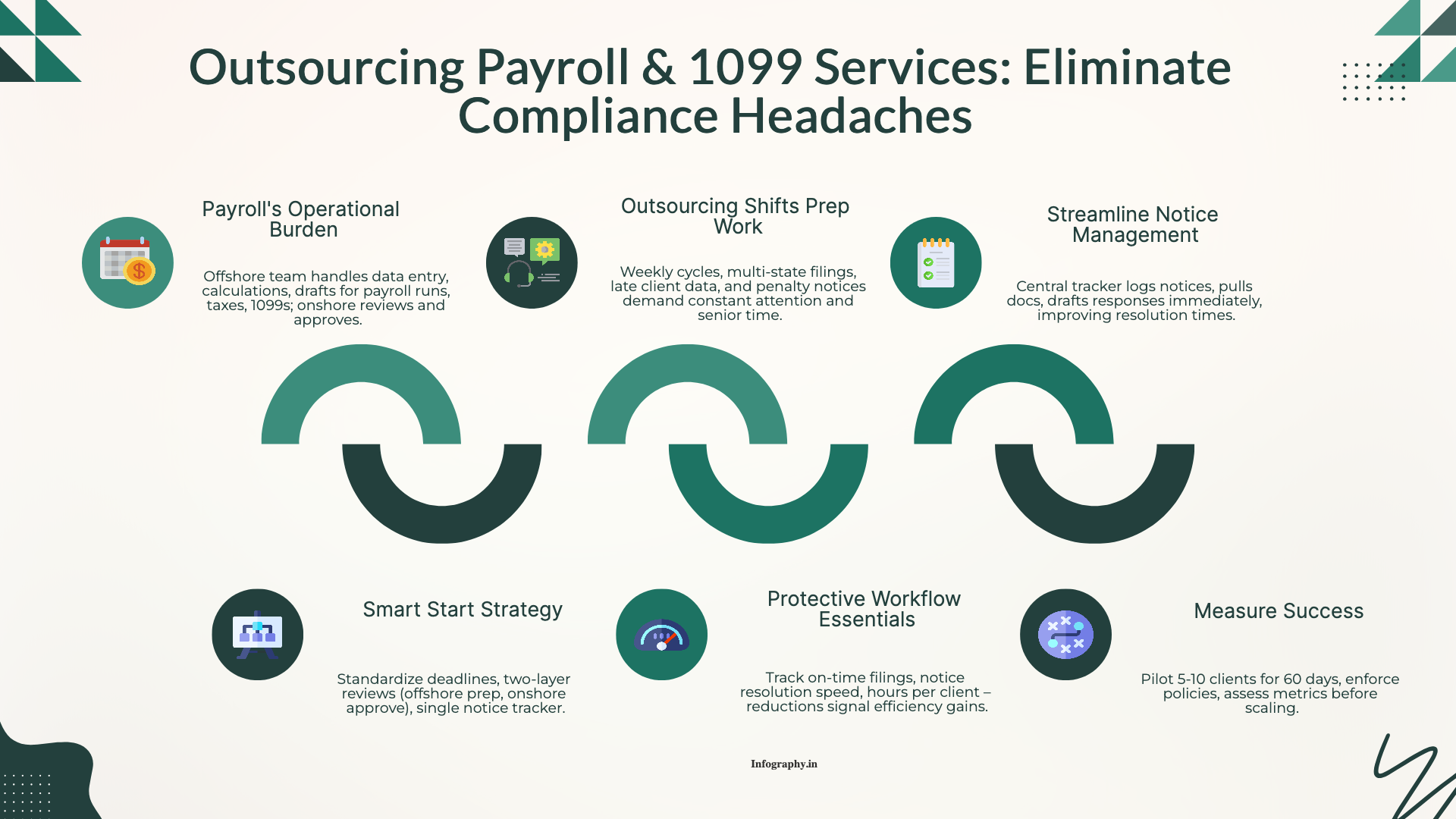

How CPA firms outsource payroll and 1099 work to reduce penalties and admin load, with a clean workflow for approvals, filings, and year-end reporting.

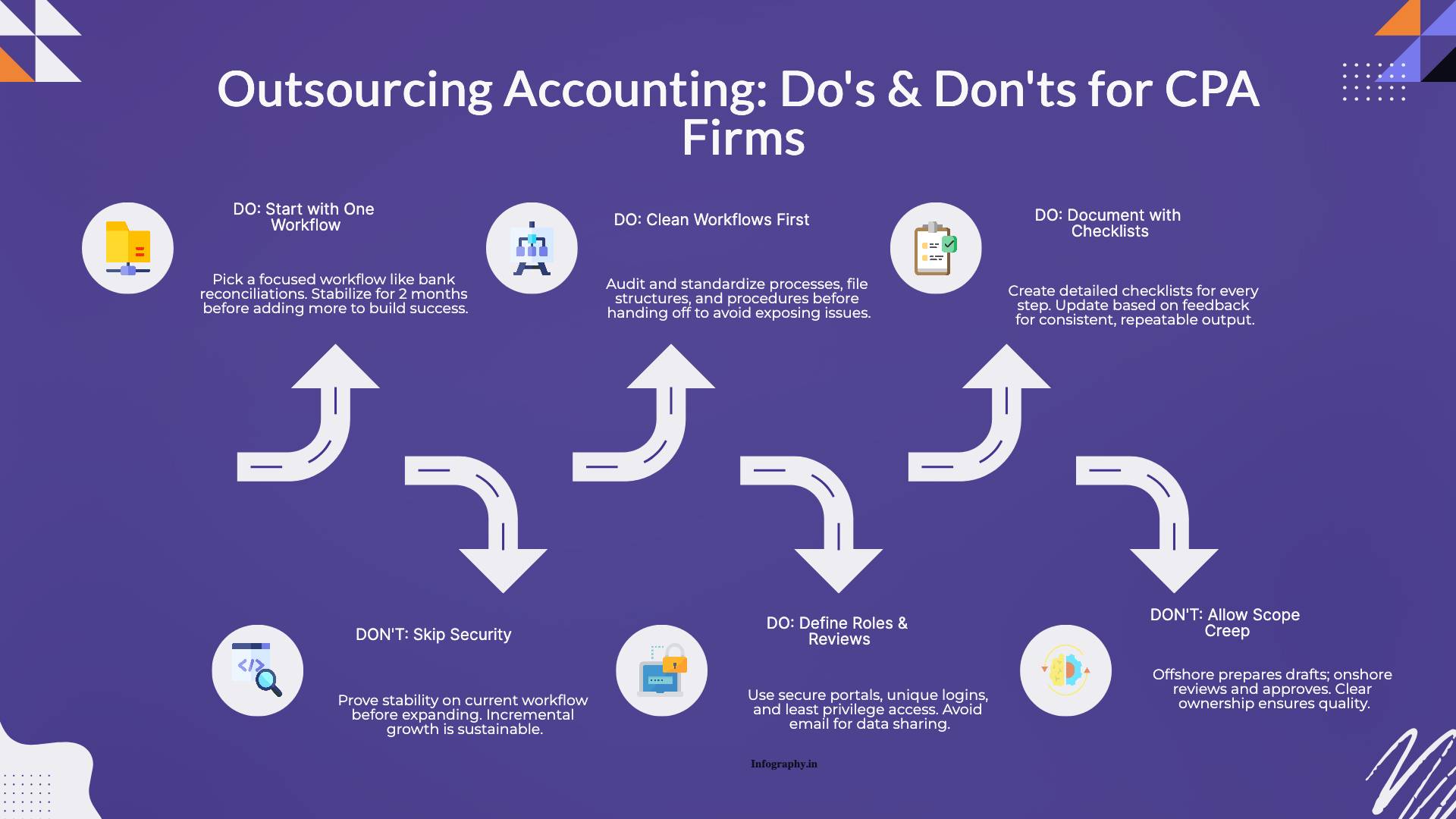

Practical do's and don'ts for CPA firms outsourcing accounting work, based on common failure points and what successful rollouts do differently.