Margin problems in CPA firms are rarely mysteries. When profits are thin, the causes are usually visible in the financials if you know where to look. Payroll costs are too high relative to revenue. Rework consumes hours that were already billed and delivered once. Scope creep creates unpaid work because the firm does not have the discipline to price additional requests. These problems persist because firms focus on revenue growth without examining the unit economics of how work is actually produced and delivered.

Outsourcing can improve margins, but only if it fundamentally changes those unit economics. Simply adding offshore capacity without restructuring workflows or protecting reclaimed time will not move margins. The improvement comes from reducing production costs, increasing capacity without proportional cost increases, and freeing senior staff to do higher-value work that commands better rates. This requires intentional design, not just a vendor contract.

Partners often frame outsourcing discussions around headcount. How much does an offshore seat cost? How many seats do we need? These questions focus on inputs rather than outputs. A better framing is to think in terms of unit economics. What does outsourcing do to the cost per tax return, cost per monthly close, or cost per audit engagement?

If an offshore team can prepare a tax workpaper package for $200 in labor cost versus $600 for an onshore junior accountant, and the quality after review is comparable, the unit economics improve by $400 per return. If the firm prepares five hundred returns annually, that is $200,000 in cost savings that flows directly to the bottom line, assuming the onshore capacity is redirected to revenue-generating work rather than left idle.

This unit cost thinking forces clarity about what work is being moved offshore, what the quality standards are, and whether the onshore team is actually freed up for higher-value work. Without this clarity, outsourcing becomes another expense line without corresponding margin improvement.

A basic margin model for a service line includes four components. Revenue per service line, which is the total fees billed for that work. Production cost, which includes the time spent by staff and any outsourcing fees for drafting, data entry, and preparation. Review cost, which is the time senior accountants, managers, and partners spend reviewing work, investigating exceptions, and ensuring quality. Rework cost, which is the time spent fixing errors, addressing client follow-ups caused by messy inputs, and redoing work that was not done correctly the first time.

Outsourcing typically targets production cost and rework cost. Production cost decreases because offshore labor rates are lower than onshore rates for comparable tasks. Rework cost decreases if the offshore team produces cleaner, more consistent deliverables than overwhelmed onshore junior staff who are making errors due to workload pressure. If outsourcing increases rework because quality is poor, margins will not improve even if production costs decrease.

Lower production cost is the most direct margin benefit. Offshore teams can draft and prepare work at a lower cost base than hiring domestic staff. The exact savings depend on the comparison being made. Comparing offshore costs to hiring a new full-time employee in a high-cost market will show larger savings than comparing to a part-time contractor in a low-cost rural area. The mechanism is consistent: offshore labor costs less for equivalent output, and that difference flows to margin if the firm does not let other costs expand to fill the gap.

More capacity without proportional cost increases improves margins through better fixed cost absorption. If the firm can take on twenty additional clients without adding domestic headcount, the fixed costs of office space, technology, and administrative support spread across more revenue. Each incremental client contributes more to the bottom line because the marginal cost of serving them is lower than the average cost.

Partners and managers doing more high-value work lifts realized rates and improves margins indirectly. If review time and cleanup time drop because the offshore team delivers cleaner work, senior staff have capacity for client-facing advisory work, business development, and strategic projects. These activities typically command higher bill rates and strengthen client relationships, which improves retention and pricing power. The margin impact is harder to quantify than direct cost savings, but it is real and often more valuable long-term.

Consider a firm with three million dollars in annual revenue and a 22 percent net margin, which translates to six hundred sixty thousand dollars in net income. The firm is at capacity and considering whether to hire another domestic staff accountant or add offshore support.

The firm adds two offshore team members at forty-two thousand dollars each annually, for a total outsourcing cost of eighty-four thousand dollars. These team members handle bookkeeping, reconciliations, and tax workpaper preparation. As a result, the firm avoids hiring one domestic role that would have cost one hundred ten thousand dollars fully loaded, including salary, benefits, payroll taxes, and training.

The firm also saves an estimated two hundred fifty manager hours per year of cleanup time because the offshore team delivers cleaner, better-documented drafts than the rushed work of overwhelmed junior staff. Valuing manager time at one hundred seventy-five dollars per hour, this represents forty-three thousand seven hundred fifty dollars in reclaimed capacity that can be redirected to client work or business development.

The net financial improvement is calculated as follows. The avoided domestic hire saves one hundred ten thousand dollars. The manager time saved is worth forty-three thousand seven hundred fifty dollars. The outsourcing cost is eighty-four thousand dollars. The net improvement is sixty-nine thousand seven hundred fifty dollars.

The new net income is seven hundred twenty-nine thousand seven hundred fifty dollars, which translates to a net margin of 24.3 percent, an improvement of 2.3 percentage points. If the firm uses the freed capacity to add revenue by taking on new clients or expanding services, the margin can improve further, though that depends on sales execution and is not automatic.

This is a worked example with simplified assumptions. Actual results depend on the specific roles, workflows, and how effectively the firm manages the transition. The principle holds: outsourcing improves margins when it reduces costs, increases capacity, and frees senior staff for higher-value work.

Margin improvements from outsourcing are not guaranteed. They can evaporate quickly if the firm does not manage the implementation carefully. Review standards that are unclear or inconsistent lead to higher rework rates, which consume the time savings that outsourcing was supposed to create. If the offshore team does not know what quality looks like, they will produce work that requires extensive correction, and the cost advantage disappears.

Partners and managers who do not protect reclaimed time find that the hours saved through outsourcing disappear into low-value meetings, administrative busywork, and unproductive activities. If the freed capacity is not deliberately redirected to client work, advisory services, or business development, the margin benefit evaporates because the firm is simply paying for offshore support while onshore staff do less revenue-generating work.

Scope creep that continues without pricing discipline erodes margins regardless of whether work is done onshore or offshore. If clients routinely request additional analysis, extra reports, or ad hoc questions without additional fees, the firm is doing unpaid work. Outsourcing makes it easier to absorb scope creep because capacity is more elastic, but absorbing unpaid work is still a margin problem. Pricing discipline is a separate issue that outsourcing does not solve.

Track unit costs before and after outsourcing to confirm that the expected savings are real. Cost per return, cost per close, and cost per engagement should decrease if outsourcing is working. If unit costs stay flat or increase, the workflow needs adjustment or the provider needs to improve quality.

Protect the time that outsourcing frees up by assigning it to specific revenue-generating activities. Block time on partner and manager calendars for client advisory calls, business development, or strategic projects. If the time is not protected and assigned, it will disappear into reactive work.

Tighten pricing discipline so scope creep does not consume the margin gains. When clients request additional work, quote a fee before proceeding. Train staff to recognize when a request is out of scope and to escalate pricing conversations rather than absorbing the work silently.

Margin improvement from outsourcing is not automatic. It requires deliberate workflow design, quality management, and operational discipline. Firms that treat outsourcing as a strategic lever for improving unit economics see real margin gains. Firms that treat it as a headcount substitution without changing how they work see minimal improvement and often end up disappointed.

A practical comparison of hiring a freelancer vs using a dedicated offshore accounting team, focusing on continuity, quality control, security, and scaling.

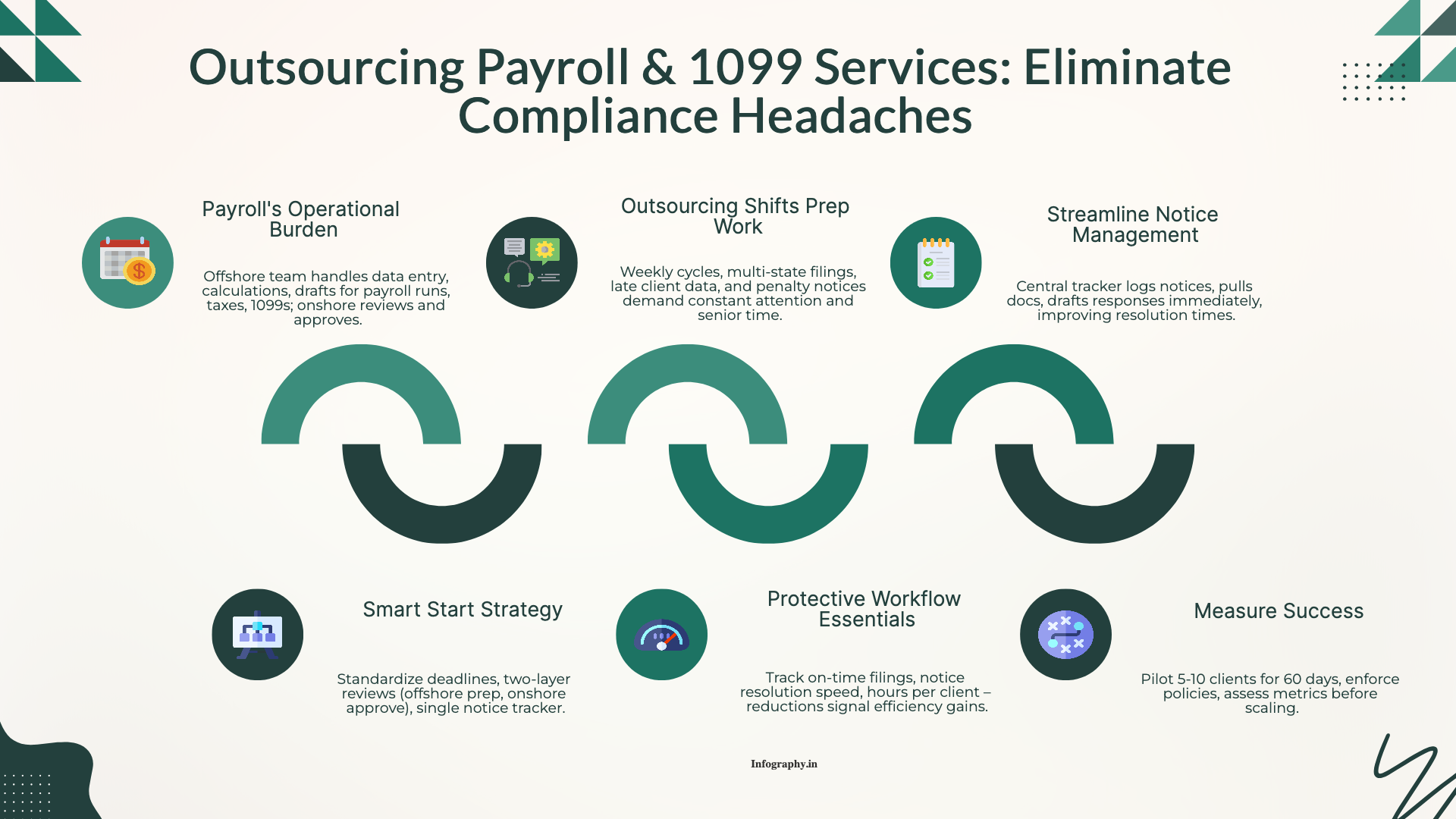

How CPA firms outsource payroll and 1099 work to reduce penalties and admin load, with a clean workflow for approvals, filings, and year-end reporting.

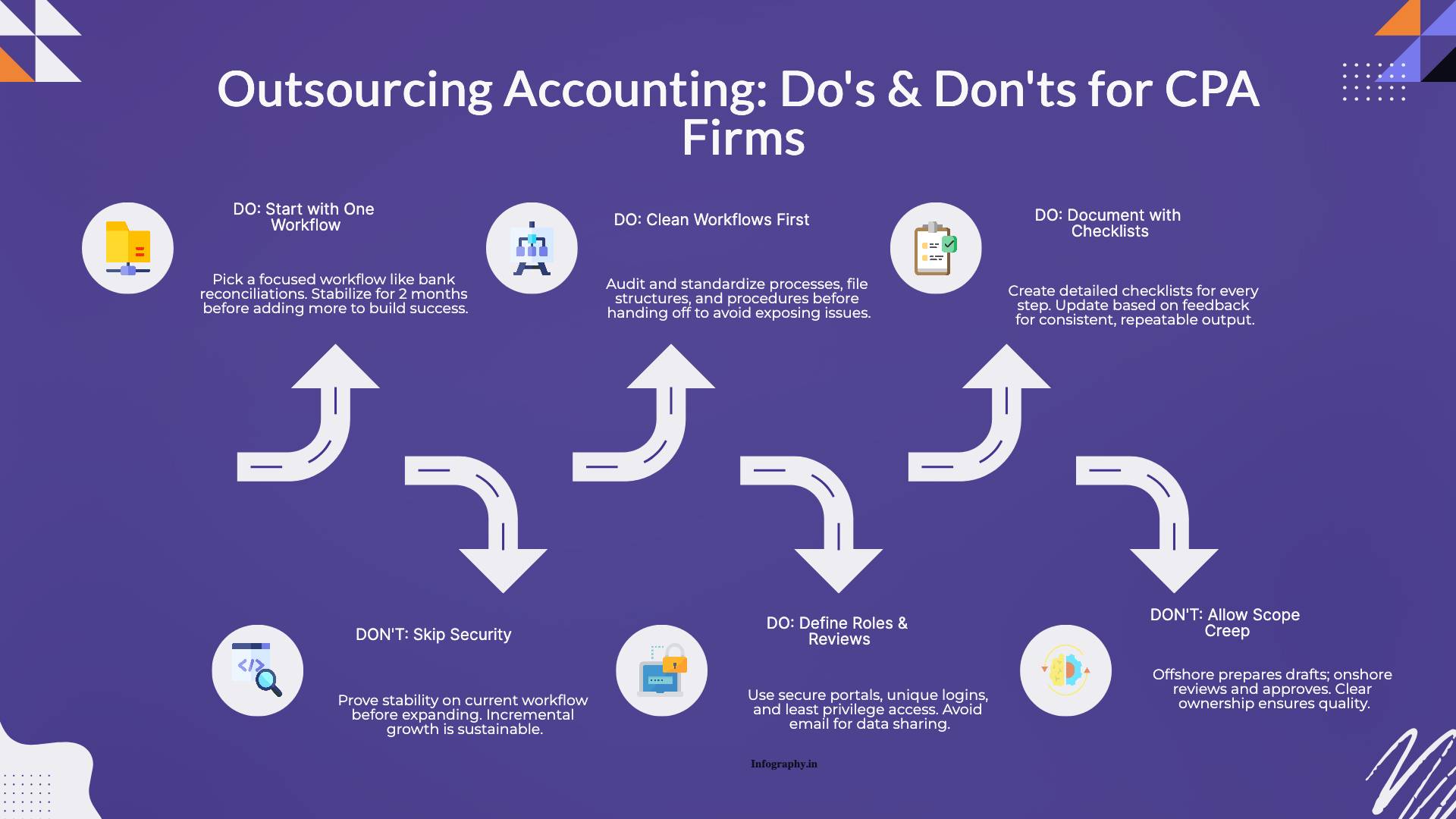

Practical do's and don'ts for CPA firms outsourcing accounting work, based on common failure points and what successful rollouts do differently.