Direct Answer: You can perform a 1031 exchange between different states under federal law, but each state has its own withholding requirements and tax rules. States like California withhold 3.33% of the sale price when you sell property there, even in a 1031 exchange. Your replacement property's location determines future state income tax obligations, not your relinquished property's state. Most states require specific forms and withholding certificates to defer state taxes during cross-state exchanges.

A real estate investor from Arizona called us last year after completing a 1031 exchange, selling an investment property in California and buying a replacement in Texas. California withheld $45,000 from his $1.35 million sale despite the federal 1031 deferral. He assumed the exchange eliminated all taxes. Six months later, he was filing for a California tax refund while scrambling to understand why Texas had different reporting requirements. That's when he learned that "tax-deferred" means different things at federal versus state levels.

Section 1031 of the Internal Revenue Code allows you to defer federal capital gains taxes when exchanging investment properties. However, the federal government doesn't control state tax laws. Each state treats 1031 exchanges differently, creating a complex web of withholding rules, filing requirements, and potential tax consequences. Since 2015, we've helped 200+ investors navigate multi-state exchanges, and the most common mistake is assuming federal tax deferral automatically covers state obligations.

The IRS allows 1031 exchanges across state lines without restriction. Your relinquished property can be located anywhere in the United States, and your replacement property can be in any other U.S. state. The properties must be like-kind (real property for real property), held for investment or business use, and equal or greater in value to defer all capital gains taxes federally.

The exchange timeline remains identical regardless of states involved: you have 45 days from closing on your relinquished property to identify up to three potential replacement properties, and 180 days total to complete the purchase. These timelines are strict and absolute, extensions are virtually never granted. Missing either deadline disqualifies your entire exchange, triggering immediate capital gains taxes on the sale.

You must use a qualified intermediary (QI) to hold your sale proceeds and facilitate the exchange. Direct receipt of funds disqualifies the exchange instantly. The QI serves as a neutral third party who holds your money in a segregated account, prepares exchange documents, and coordinates the transfer of properties. Costs typically run $800-1,500 for standard exchanges, though complex multi-property exchanges cost more.

The IRS doesn't care about state boundaries when determining like-kind qualification. Commercial property in Florida can exchange for farmland in Montana, residential rental in New York for an apartment building in Nevada, or industrial property in Ohio for retail space in Oregon. The key is that all properties must be real estate located within the United States and held for investment purposes, not personal use.

California enforces the strictest withholding rules. When you sell California real property, the state withholds 3.33% of the gross sales price unless you file Form 593-C (Real Estate Withholding Certificate) proving your 1031 exchange qualifies for deferral. Even with proper filing, California may still withhold if you're a non-resident. The withheld amount goes toward potential state income tax liability, and you must file a California return to claim any refund.

Oregon requires 8% withholding on real estate sales by non-residents unless you obtain a withholding waiver. For 1031 exchanges, file Form OR-18-WC (Oregon Withholding Certificate) before closing to reduce or eliminate withholding. Oregon is particularly aggressive about this, failure to file the certificate means 8% of your sale price gets withheld automatically, which becomes a nightmare to recover later.

New York withholds gains at rates up to 10.9% for non-residents selling New York property. To defer withholding in a 1031 exchange, file Form TP-584.1 (Combined Real Estate Transfer Tax Return) and Form IT-2663 (Nonresident Real Property Estimated Income Tax Payment Form) showing your exchange documentation. New York requires these forms at closing, so late filing isn't an option, it must happen before money changes hands.

Maryland, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Vermont, Colorado, Hawaii, Mississippi, and the District of Columbia all have their own withholding requirements for non-resident property sales. Rates range from 2% to 7% of sales price or gain. Each state has different forms, different exemption procedures, and different timelines for filing. This is where tracking tax compliance deadlines across multiple jurisdictions becomes critical for avoiding costly withholding mistakes.

States without income tax, Texas, Florida, Nevada, Washington, Wyoming, South Dakota, Tennessee, Alaska, and New Hampshire, don't withhold on 1031 exchanges because they have no state capital gains taxes to collect. However, you still face tax consequences in your state of residence if you live in an income tax state, even if your property is in a no-tax state.

Your state of residence matters more than your property's location for long-term tax planning. If you're a California resident who exchanges a California property for a Texas property, California still considers you a California taxpayer. When you eventually sell the Texas property without doing another exchange, California will tax the accumulated capital gains because you were a California resident during the holding period.

Some states have "clawback" provisions that tax deferred gains if you move out of state before selling. California aggressively pursues former residents who deferred gains on California property, moved to a no-tax state, and then sold the replacement property. The California Franchise Tax Board argues that gains accumulated while you were a California resident remain taxable by California, even if you've since relocated.

States differ on how they treat exchanges into their jurisdiction from other states. If you're a Texas resident who sells a California property and buys a Texas replacement property through a 1031 exchange, Texas doesn't care because Texas has no income tax. But California will withhold 3.33% at closing, and you'll need to file a California non-resident return to claim a refund of the withholding.

The timing of residency changes creates complex scenarios. An investor who lives in Oregon, exchanges Oregon property for Arizona property, and then moves to Arizona before selling faces questions about which state has taxing rights. Generally, the state where you were a resident when the gain accrued has taxing authority, but each state interprets "accrual" differently. Some look at when you acquired the original property, others at when you sold the replacement property.

Multi-state exchanges require careful documentation of your residency status at each transaction point. Investors who change residency frequently should maintain records proving where they lived during each property ownership period. This becomes essential when states dispute taxing rights years after transactions close.

California requires Form 593-C (Real Estate Withholding Certificate) submitted to the Franchise Tax Board before or at closing. Your qualified intermediary must sign this form confirming the 1031 exchange structure. Include your exchange agreement, identification notice, and proof that the transaction meets IRC Section 1031 requirements. California processes these requests within 20 days if filed properly, but mistakes cause delays that can disrupt your closing.

Oregon's Form OR-18-WC (Withholding Certificate for Oregon Real Property Transfers) needs submission at least seven business days before closing to avoid mandatory 8% withholding. Attach your exchange documentation, purchase agreement for replacement property, and proof of qualified intermediary engagement. Oregon is strict about timing, submit too late, and withholding happens automatically without appeal.

New York's combination of Form TP-584.1 and IT-2663 requires completion at closing. These forms integrate into your closing documents, so your attorney and qualified intermediary must coordinate carefully. New York wants to see your 45-day identification letter, purchase contract for replacement property, and qualified intermediary agreement. Missing any component can trigger full withholding that takes months to recover.

Most states accept a standard withholding certificate or exemption application, but formats vary. Some states have specific forms, others accept a letter with required elements, and a few require notarization. Your qualified intermediary should know these requirements, but ultimately you're responsible for ensuring proper filing. Relying solely on your QI without verification has caused problems for investors who discovered their QI wasn't familiar with specific state rules.

The IRS Form 8824 (Like-Kind Exchanges) goes on your federal tax return but doesn't satisfy state requirements. You must file separate state forms in addition to federal reporting. States want real-time documentation at closing, not just year-end tax return reporting. This means preparing state-specific paperwork before your closing date, not after.

Exchanging from California to a no-tax state like Texas or Florida provides long-term benefits but creates immediate withholding complications. California withholds 3.33% of your sales price at closing even with proper 1031 paperwork. You'll need to file a California non-resident return the following year to recover this withholding, assuming your exchange was executed properly and no gain was recognized.

If you're still a California resident when you complete this exchange, California's benefit disappears. You remain a California taxpayer on all income regardless of where your properties are located. The advantage only materializes if you change residency to a no-tax state before selling the replacement property. Many investors misunderstand this, they think exchanging California property for Texas property automatically reduces their tax burden, but it doesn't unless they move.

High-tax states like New York (10.9%), California (13.3%), and Oregon (9.9%) make 1031 exchanges particularly valuable for deferring substantial tax bills. A $500,000 capital gain in California triggers $66,500 in state taxes plus federal taxes. Deferring this through a 1031 exchange preserves capital for your next investment. However, the tax doesn't disappear, it's deferred until you eventually sell without exchanging.

Some investors use a strategy of continually exchanging properties while gradually moving to a no-tax state. They establish residency in Texas, Florida, or Nevada, wait to establish bona fide residency (typically 1-2 years with clear connections to the new state), and then sell their replacement property. This strategy requires careful planning with professional tax advisory services because states scrutinize these transactions for attempts to avoid legitimate tax obligations.

Nine states follow community property rules: Arizona, California, Idaho, Louisiana, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin. In these states, property acquired during marriage belongs equally to both spouses regardless of whose name is on the title. This affects 1031 exchanges when one spouse wants to exchange but the other doesn't, or when couples divorce during an exchange period.

When exchanging from a community property state to a common law state, or vice versa, the character of ownership can change. Community property exchanged for separate property in a common law state might create unexpected tax consequences upon divorce or death. The step-up basis rules that benefit community property (both halves get stepped up at death) don't apply the same way to separate property in common law states.

Married couples must both sign exchange documents in community property states, even if only one spouse's name appears on title. Failure to obtain both signatures can invalidate the exchange or create partial recognition of gain. This becomes complicated when couples live in different states due to work situations or when they move states during the 180-day exchange period.

Divorce during a 1031 exchange creates nightmares. If you're 60 days into your 180-day exchange period and file for divorce, the property division issues can derail your exchange entirely. Some divorcing couples complete the exchange first, then divide the replacement property later. Others split the exchange, with each spouse identifying separate replacement properties. Both approaches require careful legal and tax planning.

The most expensive mistake is ignoring state withholding requirements. Investors assume their qualified intermediary handles everything, but QIs focus on federal compliance. State withholding certificates are your responsibility to research and file. Missing a filing deadline in California, Oregon, or New York means automatic withholding that takes 6-18 months to recover through state tax return processing.

Changing residency mid-exchange without considering tax implications causes problems. Moving from California to Texas after selling your California property but before buying your Texas replacement property creates confusion about which state has taxing authority. California may argue you were a resident during the "sale" portion of the exchange, while Texas has no tax involvement. Proper timing of residency changes requires advance planning, not reactive decision-making.

Assuming no-tax states are always better overlooks other factors. Florida has no income tax but charges high property insurance rates. Texas has no income tax but high property taxes. Nevada has no income tax but charges higher business license fees. When evaluating which state to exchange into, consider the total tax and regulatory burden, not just income tax rates.

Failing to document residency properly leads to dual-state taxation disputes. If California and Arizona both claim you as a resident, you could face taxes in both states on the same income. Maintain driver's licenses, voter registration, professional licenses, and primary residence documentation showing clear residency status. Some investors benefit from filing state tax returns in their old state showing "part-year resident" status to establish a clean break.

Relying on outdated information about state 1031 rules creates compliance failures. States change their withholding requirements, forms, and procedures regularly. Information from 2022 may not reflect current 2025 rules. Always verify current requirements directly with state revenue departments or through professional tax compliance guidance before closing.

If you're moving from a no-tax state to a high-tax state, evaluate whether deferral makes sense. Exchanging from Florida property (no state tax) to California property (13.3% state tax) locks you into California's high tax environment. You might be better off paying federal capital gains taxes in Florida, taking your proceeds to California, and starting fresh without the accumulated deferred gain following you.

Small exchanges with modest gains sometimes aren't worth the complexity. If your capital gain is $30,000 and you're exchanging between complex states like California and New York, the combined cost of qualified intermediary fees ($1,200), state withholding hassles, multi-state tax return preparation ($800-1,500), and administrative burden might approach the tax you'd save. For small gains, paying the tax and moving on can be smarter.

When you plan to sell the replacement property within 2-3 years, deferral provides limited benefit. The accumulated deferred gain from your original property plus the new gain from the replacement property create a large tax bill when you eventually sell. If you know you'll exit real estate investing soon, taking the tax hit now at potentially lower tax rates might beat deferring into an unknown future tax environment.

If proper documentation requirements exceed your organizational capabilities, don't attempt a multi-state exchange. These transactions require meticulous record-keeping, multiple state forms, coordinated timing between closings, and careful compliance with both federal and state rules. Investors who struggle with paperwork and deadlines often fail to execute exchanges properly, leading to partial or complete gain recognition and tax penalties.

Yes, federal law allows 1031 exchanges across state lines without restriction. However, California will withhold 3.33% of your sales price at closing unless you file Form 593-C proving your 1031 exchange qualifies. You'll need to file a California non-resident tax return to recover this withholding. Florida has no state income tax, so no issues arise on the purchase side.

It depends on your residency. If you're a California resident exchanging California property for Texas property, you remain a California taxpayer. California won't tax you on the exchange itself (properly deferred), but will eventually tax the gain when you sell the Texas property. You only escape California taxes by establishing bona fide Texas residency before selling the replacement property.

The state automatically withholds at their statutory rate, 3.33% in California, 8% in Oregon, up to 10.9% in New York. This withholding happens at closing and comes from your sale proceeds. You'll need to file a state tax return showing your 1031 exchange to claim a refund, which typically takes 6-18 months. The withheld amount doesn't earn interest, so you lose the time value of that money.

Most states require 183+ days of physical presence plus establishment of clear residency indicators: driver's license, voter registration, professional licenses, bank accounts, and primary residence. California is particularly aggressive about claiming former residents remain California taxpayers, requiring clear evidence you've established a new domicile elsewhere. Consult tax advisors about specific state requirements, each state defines residency differently.

Yes, you can sell properties in California, Oregon, and Texas, then use the combined proceeds to buy one replacement property in Arizona. This works under federal 1031 rules. However, you'll face withholding requirements in California and Oregon, need to file multiple state tax returns, and must ensure the replacement property value equals or exceeds the combined value of all relinquished properties to defer all gains.

You're ultimately responsible for state compliance, not your QI. Many qualified intermediaries focus on federal requirements and don't provide state-specific guidance. Research state requirements yourself or hire a tax advisor who specializes in multi-state exchanges. Don't assume your QI knows every state's withholding rules, California, Oregon, and New York have particularly complex requirements that generic QIs often miss.

Yes, in nine community property states (Arizona, California, Idaho, Louisiana, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Washington, Wisconsin), both spouses must sign exchange documents even if only one name is on title. Divorce during an exchange can invalidate the transaction. When exchanging between community property and common law states, the character of ownership may change, affecting future tax consequences upon death or divorce.

Yes, you must file returns in states where you sold property (if they withheld taxes or if you're a resident) and potentially in states where you bought property (if you're a non-resident of that state and it has income tax). Many investors need 2-3 state returns plus their federal return after cross-state exchanges. Professional tax preparation for multi-state exchanges typically costs $800-1,500 annually, but prevents costly mistakes.

Cross-state 1031 exchanges work perfectly under federal law but require careful attention to state-specific withholding, filing, and compliance requirements. The key is researching state rules before your exchange, not after closing when withholding has already occurred. California, Oregon, and New York have particularly aggressive withholding systems that catch uninformed investors off guard.

Your strategy should consider both immediate withholding issues and long-term residency planning. Exchanging into a no-tax state only provides benefits if you plan to establish residency there before selling. Otherwise, your home state will eventually tax the deferred gains. Most successful multi-state exchanges involve investors who research requirements early, file all necessary forms before closing deadlines, and work with qualified intermediaries familiar with their specific state combinations.

Since 2015, Madras Accountancy has guided 200+ investors through complex multi-state 1031 exchanges, helping them navigate withholding requirements, file proper state forms, and structure exchanges that defer both federal and state taxes legally. If you're planning a cross-state exchange and need expert guidance on state-specific compliance requirements, our tax team can help you avoid costly withholding mistakes and maximize your tax deferral benefits.

A practical comparison of hiring a freelancer vs using a dedicated offshore accounting team, focusing on continuity, quality control, security, and scaling.

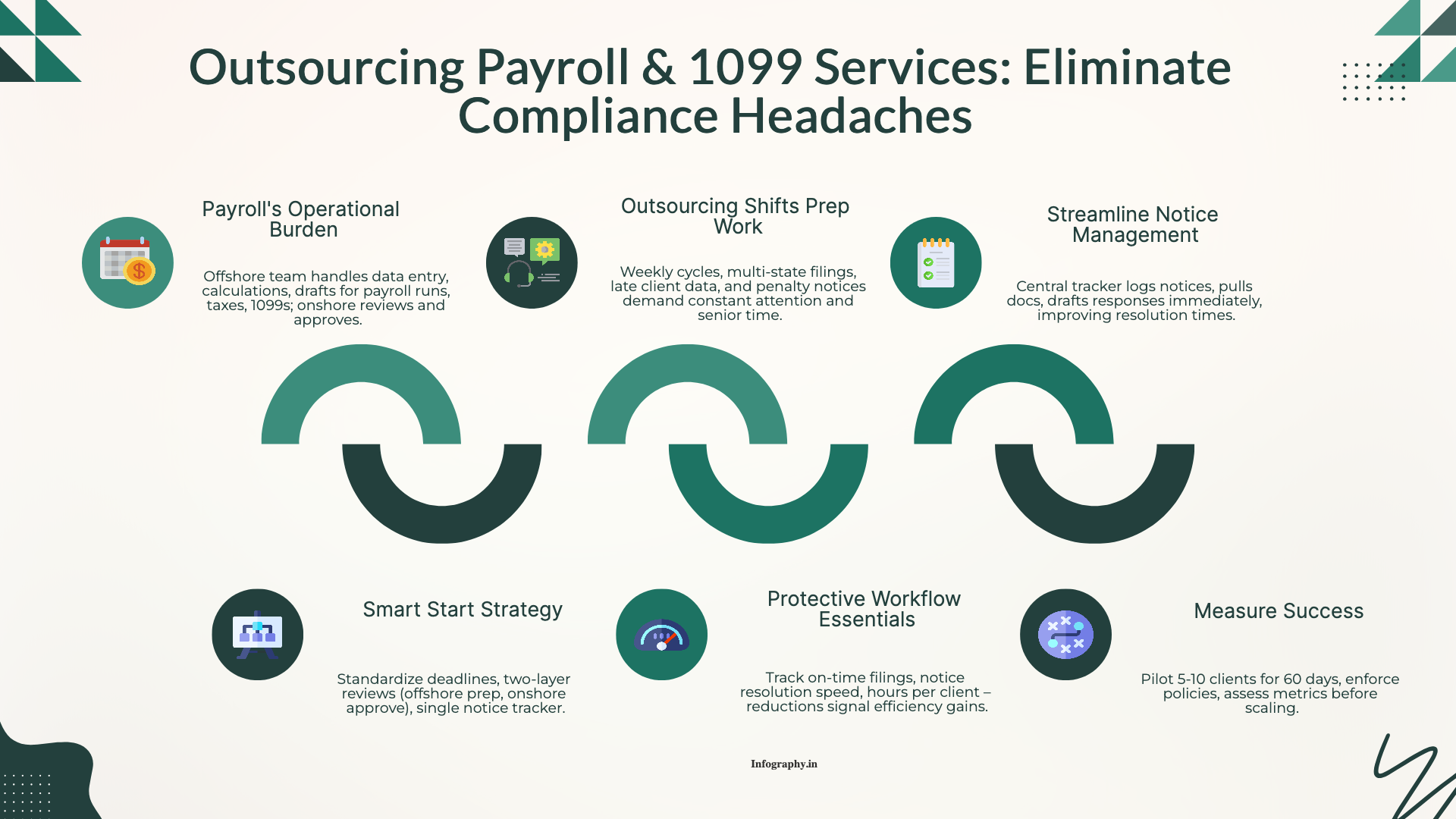

How CPA firms outsource payroll and 1099 work to reduce penalties and admin load, with a clean workflow for approvals, filings, and year-end reporting.

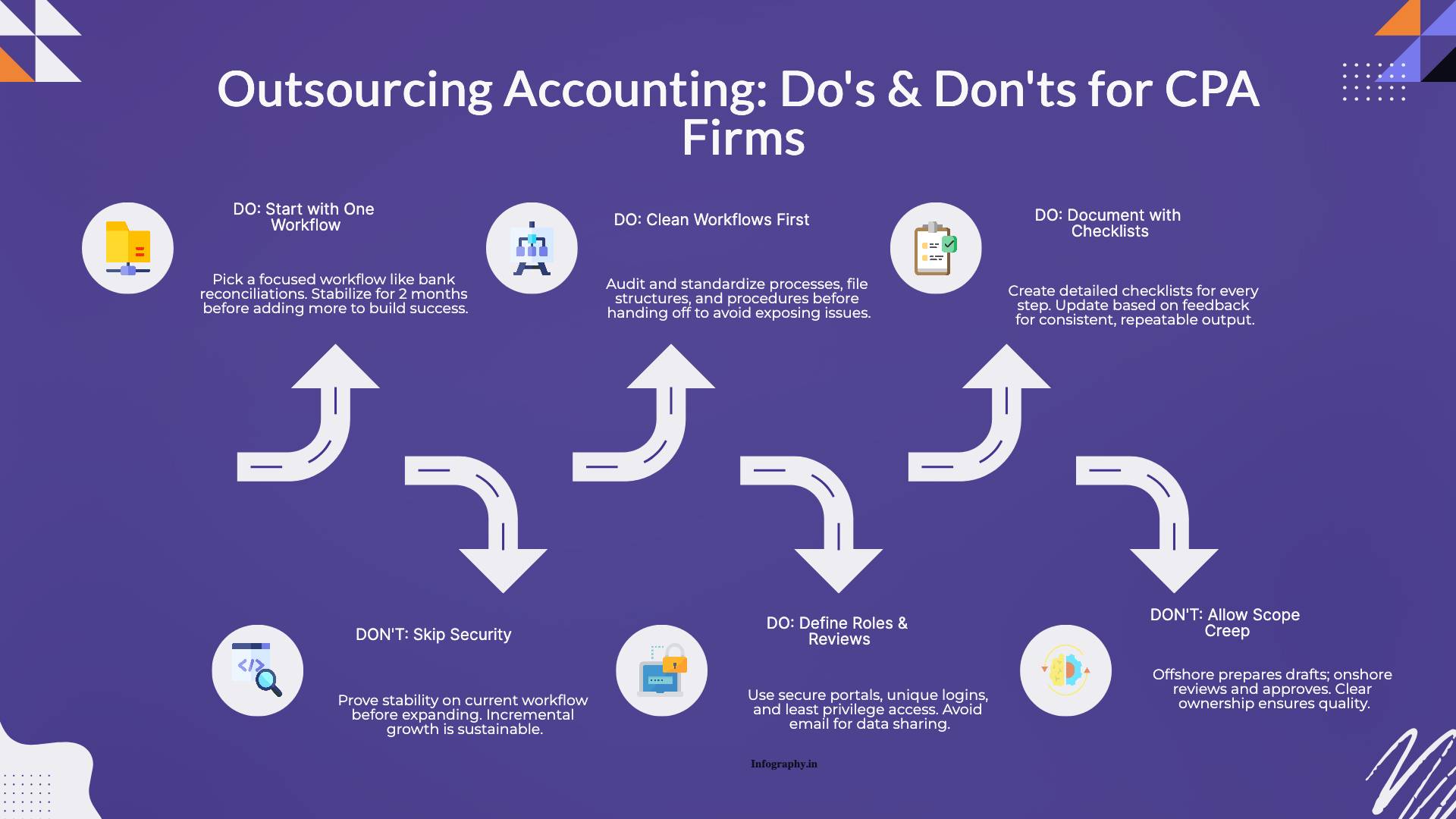

Practical do's and don'ts for CPA firms outsourcing accounting work, based on common failure points and what successful rollouts do differently.