The first warning sign was subtle. The calendar stopped functioning as a planning tool and turned into a wall of back-to-back commitments with no breathing room between them. Partners could not find time for business development. Managers were too busy fixing errors to coach junior staff. The firm was running hard but not growing, trapped in a cycle where all capacity went to existing work with nothing left for improvement or expansion.

This is a realistic case study based on patterns observed across small and mid-sized CPA firms. The numbers are worked examples using typical cost structures and billing rates, not specific firm data. Your rates and efficiency will differ, but the mechanism and the lessons apply broadly.

The firm employed twelve people total: two partners, three managers, six staff accountants, and one administrative person. The service mix included tax preparation, monthly bookkeeping and close support, and a small amount of advisory work that partners wished they could expand but never had time for. The client base was stable and loyal. The problem was not client satisfaction. The problem was capacity and the daily grind it created.

Monthly closes consistently slipped from the target of day ten to day eighteen or later. This slippage was not caused by one dramatic bottleneck. It resulted from accumulated small delays. Reconciliations took longer because junior staff made errors that required manager correction. Client follow-ups took days instead of hours because everyone was too busy to respond promptly. The close process that should have been routine became a scramble every month.

Managers spent their evenings cleaning up workpapers that should have been completed correctly during the day. The cleanup work was not technically complex. It was repetitive correction of categorization errors, formatting issues, and missing documentation. This low-value work consumed manager time that should have gone to review, training, and client advisory.

Partners reviewed tax returns late at night after client meetings and administrative work consumed their days. The next morning, they were too tired to focus on business development or strategic planning. The firm maintained revenue but could not grow because partner capacity for sales and advisory work did not exist.

The firm did not attempt to outsource their entire operation. They picked work with clear inputs, documented procedures, and measurable outputs. Bank and credit card reconciliations were first because the process was straightforward and the quality could be verified easily. Transaction coding and cleanup came next because consistent coding was essential to financial statement quality. Draft financial statement preparation followed once the bookkeeping was stable. Basic tax workpaper assembly for recurring clients rounded out the initial scope.

The offshore team delivered drafts and supporting documentation. A US senior accountant reviewed every deliverable for accuracy and completeness. The review process remained entirely onshore, maintaining quality control and professional accountability.

Before implementing offshore support, the firm spent approximately eighty-five hours per month across staff and senior accountants on monthly bookkeeping and close work for their client base. Manager time spent on rework and cleanup added another eighteen hours per month. Partner review spillover, where partners handled work that should have stayed at manager level, added ten hours per month. The total onshore time investment was one hundred thirteen hours per month.

After offshore support stabilized over the first sixty days, the time allocation changed. The offshore team handled most transaction preparation and draft work, investing approximately fifty-five hours per month. US staff handled exceptions, client questions, and review, requiring twenty hours per month. Manager review time dropped to ten hours per month because drafts arrived cleaner and more complete. Partner spillover dropped to four hours per month because managers were no longer overwhelmed. The total onshore time investment fell to eighty-nine hours per month.

The net time savings were twenty-four hours per month, or approximately two hundred eighty-eight hours annually. This represents freed onshore capacity that could be redirected to higher-value work if the firm protected it deliberately.

Saved hours do not automatically convert to revenue. Time that is freed but not protected disappears into low-value meetings, administrative busywork, and reactive tasks. The firm had to make deliberate decisions about how to use the capacity.

They established two rules to protect the freed time. Managers were directed to use reclaimed time for substantive review and client-facing work, not for refilling their calendars with internal meetings. Partners committed to blocking two windows per week for business development calls and client advisory sessions. These windows were treated as client appointments that could not be moved for internal priorities.

The revenue conversion required discipline. Assuming the firm could convert forty percent of the two hundred eighty-eight saved hours into billable work, that represented one hundred fifteen billable hours annually. Using an average realized billing rate of two hundred twenty-five dollars per hour across a mix of advisory, tax planning, and client communication work, the estimated added annual revenue was approximately twenty-five thousand eight hundred seventy-five dollars.

This is not a dramatic number. It is what happens when saved time is protected, scheduled deliberately, and directed toward client-facing activities that can be billed. The number would be higher if the firm was more aggressive about converting capacity to revenue, but even modest conversion creates meaningful financial impact.

Two changes occurred that were not captured in the initial time savings spreadsheet but mattered significantly to firm operations and staff satisfaction.

Month-end close became predictable again. By month three of working with the offshore team, closes were consistently completed by day ten or eleven rather than slipping to day eighteen. This improvement did not result from people working faster. It resulted from work arriving in cleaner condition with fewer missing items, incomplete reconciliations, or categorization errors that required correction. Predictable close timelines reduced stress for both staff and clients.

Overtime dropped measurably. In the six weeks before implementing offshore support, staff averaged approximately fifty-two hours per week during peak periods. After the offshore workflow stabilized, average hours dropped to approximately forty-five hours per week during the same calendar periods. The firm was still busy, but it stopped feeling like the team was perpetually behind and catching up. The psychological benefit of this shift was significant even though absolute hours remained above forty per week.

The time and revenue gains were not accidental. They resulted from three deliberate, unglamorous decisions that created discipline and consistency.

The firm wrote a detailed checklist for month-end close and used it every time without exception. The checklist listed every required step, every support document that must be attached, and every quality check that must be performed before work was submitted for review. This consistency allowed the offshore team to learn quickly and produce work that met standards reliably.

They defined clear review rules including what types of transactions required supporting documentation, what materiality thresholds applied to follow-up questions, and what format deliverables should take. These rules eliminated ambiguity and reduced the back-and-forth that consumes time without adding value.

They held a short weekly meeting focused exclusively on exceptions and process improvements, not status updates. If the tracker showed status accurately, reading it aloud in a meeting was waste. The meeting addressed recurring errors, discussed edge cases, and updated procedures to prevent future issues. This discipline kept the workflow improving rather than stagnating.

Start by picking one workflow to outsource. Monthly bookkeeping close is a common choice because results show up quickly and the work is recurring, making it easy to measure improvement over multiple cycles.

Measure current hours for four weeks to establish a baseline. Do not guess or estimate. Track actual time spent by role and by task. This measurement reveals where time is going and where savings are most achievable.

Set a specific target that can be measured objectively. Save twenty hours per month or achieve close by day ten are examples of clear targets. Vague goals like work smarter or improve efficiency are not measurable and do not create accountability.

Protect the reclaimed time on calendars or it will disappear. Block specific windows for the activities you want freed capacity to enable, whether that is client advisory calls, business development, or training. If the time is not protected and assigned, it fills with reactive work and the benefit evaporates.

The real lesson is that offshore support creates the potential for time savings and revenue growth. Realizing that potential requires management discipline to measure results, protect freed capacity, and direct it toward activities that create value for clients and the firm. The hours can be saved. Turning them into revenue is a deliberate choice, not an automatic outcome.

A practical comparison of hiring a freelancer vs using a dedicated offshore accounting team, focusing on continuity, quality control, security, and scaling.

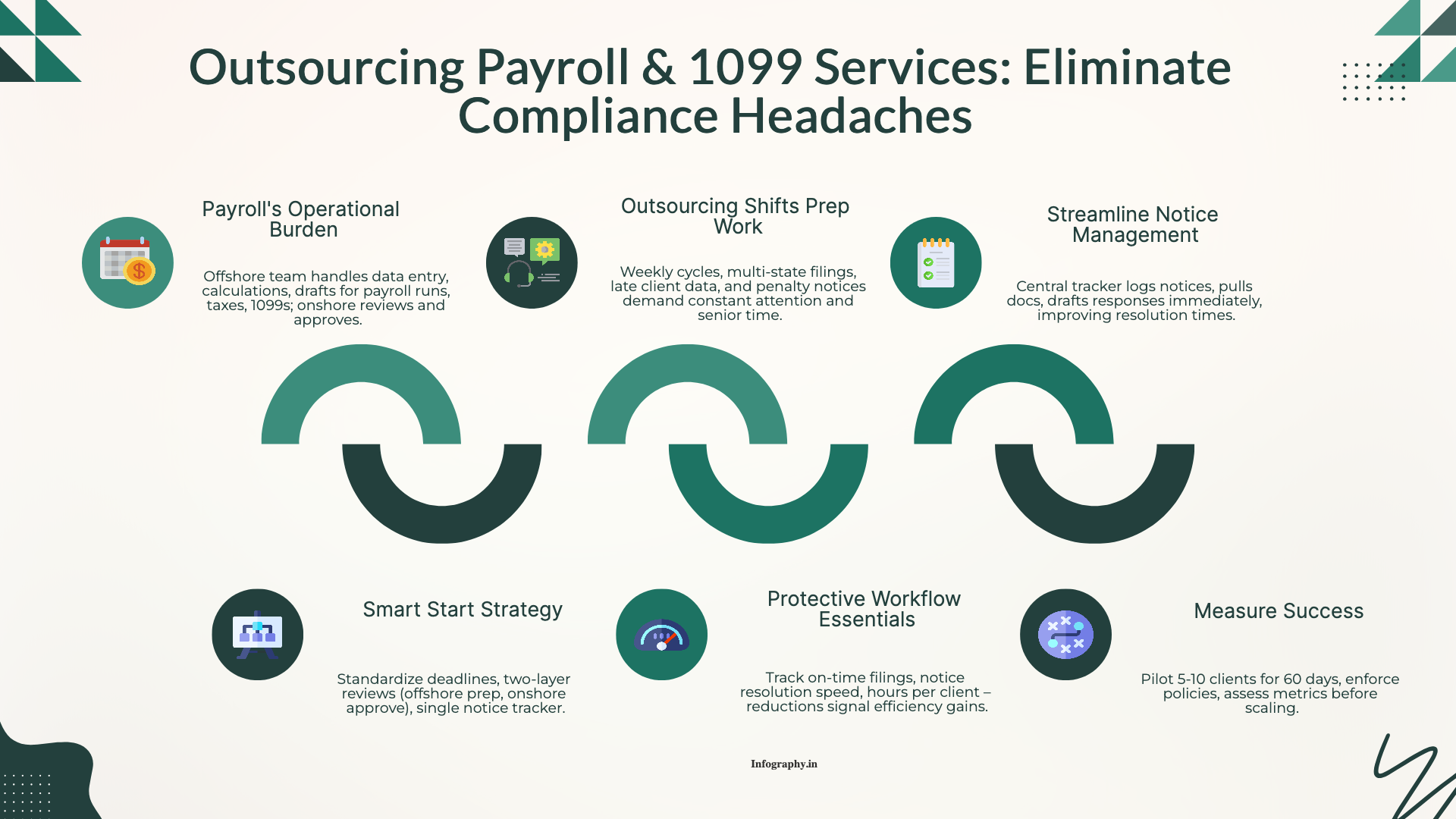

How CPA firms outsource payroll and 1099 work to reduce penalties and admin load, with a clean workflow for approvals, filings, and year-end reporting.

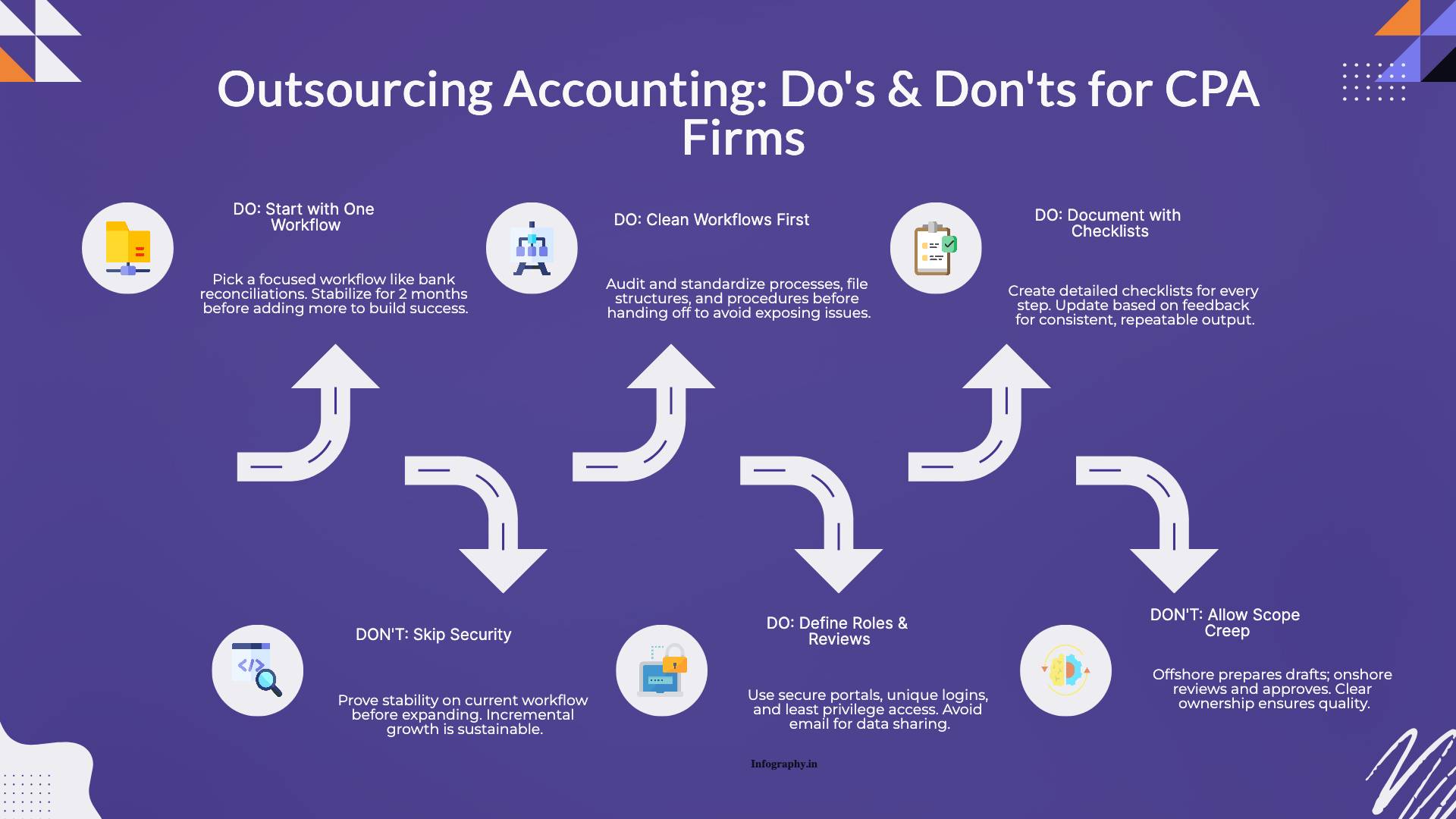

Practical do's and don'ts for CPA firms outsourcing accounting work, based on common failure points and what successful rollouts do differently.